Fayetteville has reason to celebrate. Remember this moment.

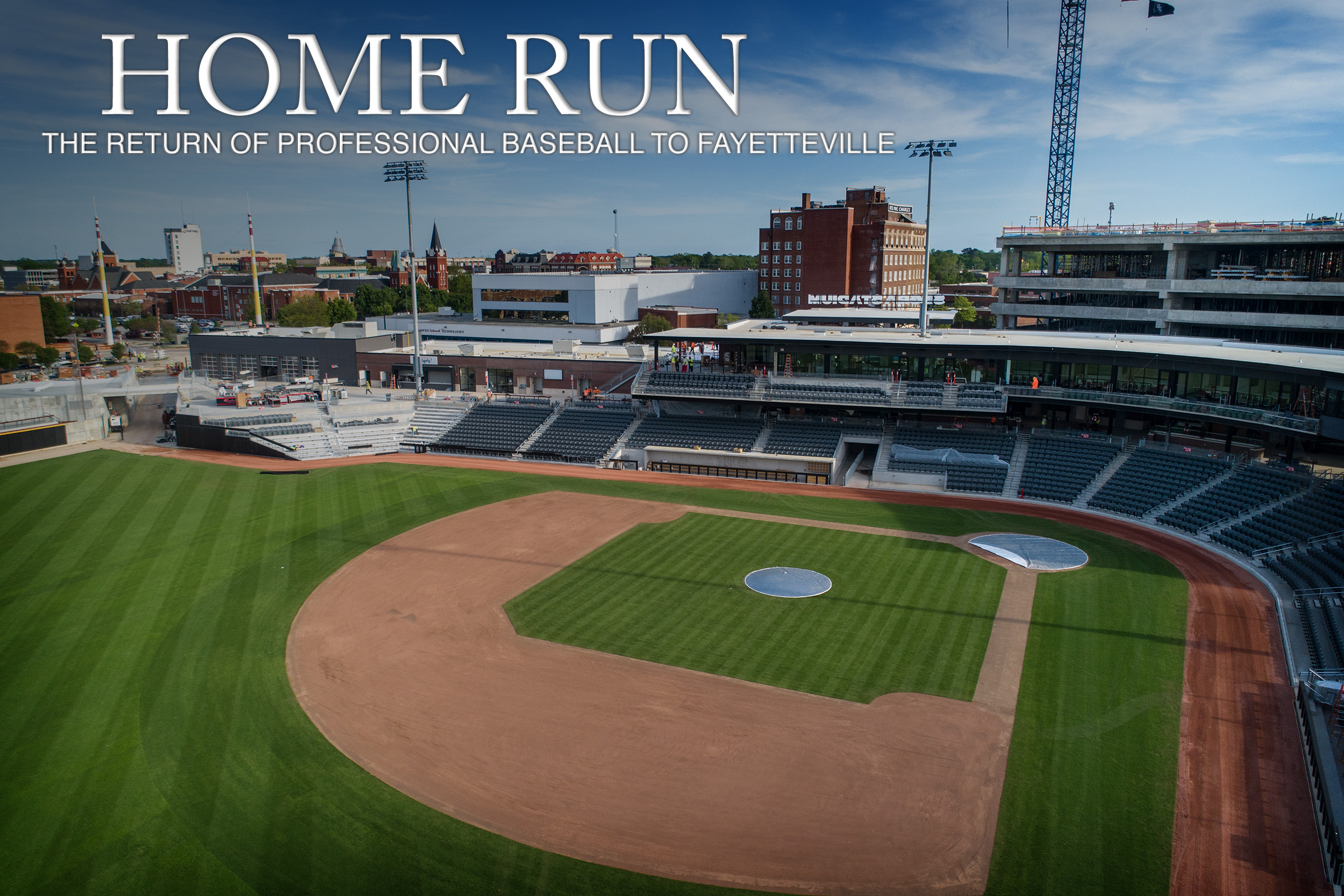

The opening of Segra Stadium in downtown is a momentous chapter in our city's history, and not just because it represents the return of professional baseball. The $40 million stadium is the engine driving more than $120 million in public and private investment in downtown, the largest such project ever in Fayetteville. The stadium will be one of the first things that businesses, recruiters and real estate companies brag about when describing quality of life in Fayetteville and why industries should consider our market. Perhaps most important, the stadium signals that Fayetteville is finally willing to think big, take some risks and boldly demand that we deserve better. We are not the Fayetteville of 40 years ago, or even 20 years ago. When you hear the first crack of the bat April 18, you'll remember it as the moment Fayetteville took control of its own destiny and hit a home run.

Fayetteville's century of baseball history

Babe Ruth while he was in Fayetteville. [File]

The tale of Babe Ruth's first professional home run is the most famous chapter of Fayetteville's baseball history. But the link between the city and professional baseball didn't begin or end with Ruth's historic blast on March 7, 1914, at the old Cape Fear Fair Grounds.

Jim Thorpe, who was voted the greatest athlete of the 20th Century, spent time playing minor league baseball in Fayetteville in 1909. Calvin Koonce, the 1969 World Series champion, was born in Fayetteville and raised in Hope Mills. And just three years ago, Fort Bragg hosted the first regular-season game played on a U.S. military installation.

[PHOTOS: From Fayetteville to 'The Show']

Fayetteville has been home to no fewer than eight minor league clubs, a number that will increase to nine as the Advanced Class A Carolina League Fayetteville Woodpeckers make their debut in 2019. Those previous minor league franchises helped develop future Major League all-stars such as Smoky Burgess, Brandon Phillips, Francisco Cordero, Milton Bradley and Jose Lima.

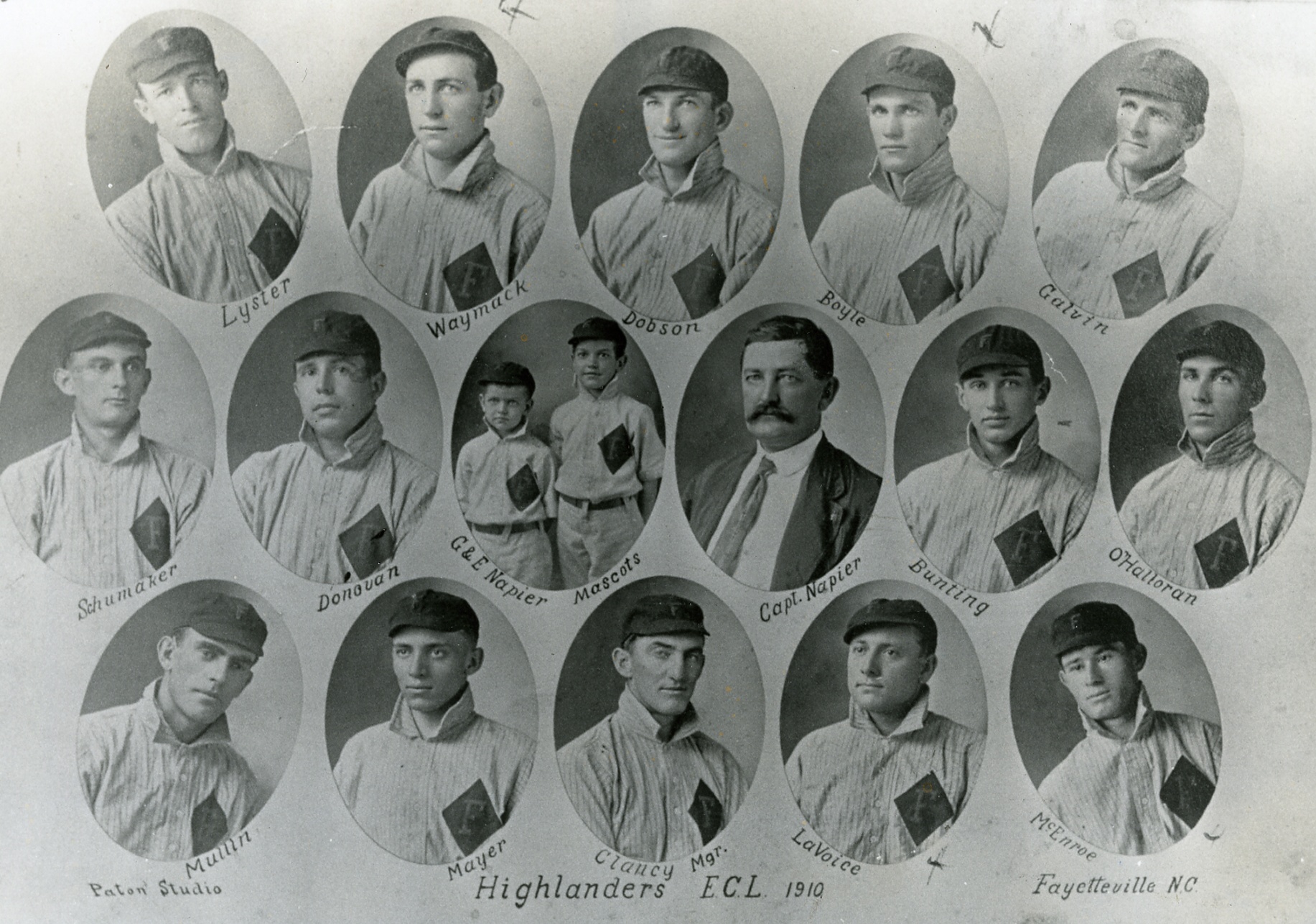

The city's earliest documented professional team was the Fayetteville Highlanders, a Class D Eastern Carolina League franchise that operated from 1909 to 1910. The Highlanders played at the Cape Fear Fair Grounds, which was a few yards off Gillespie Street.

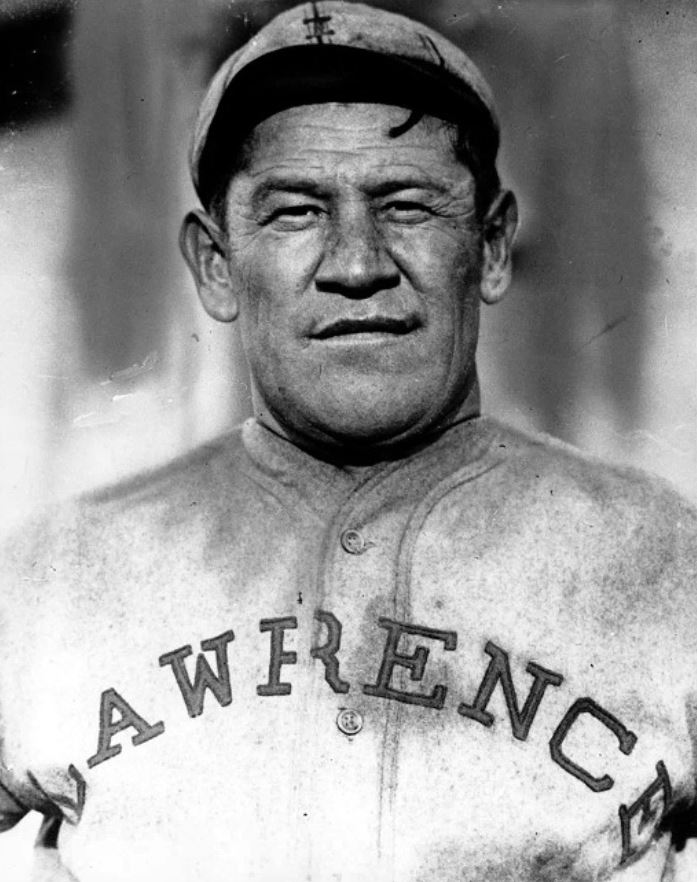

Thorpe was an unknown student attending the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania when he came South in the summer of 1909 to earn extra money doing farm work in Rocky Mount. While there, Thorpe was talked into quitting the job to play baseball for the Railroaders of the professional Class D Eastern Carolina League. Thorpe was paid weekly for room and board in 1909 and part of 1910 with the Railroaders before being traded to the Highlanders about midseason.

Thorpe batted .250 in 16 games as the Highlanders won the Eastern Carolina title. His lengthy home run in an exhibition game at the fairgrounds is still part of local lore.

Two summers later in Stockholm, Sweden, Thorpe claimed Olympic gold medals in the decathlon and pentathlon. Hailed as a national hero, Thorpe was honored upon his return to the United States with a ticker-tape parade in New York.

But a controversy tied to his days in Fayetteville cost Thorpe his Olympic medals a year later.

During that time, professional athletes were not allowed to compete in the Olympics. Because he'd accepted payment for playing baseball in Rocky Mount and Fayetteville in 1909-10, Thorpe was considered a professional. Thorpe didn't believe he was doing anything wrong because he'd witnessed other college athletes doing the same thing.

A story appearing in a Massachusetts newspaper in 1913 revealed Thorpe's secret based on statements from Charles C.A. Clancy, who, according to several published reports, had managed the Fayetteville team.

The International Olympic Commission eventually stripped Thorpe of his gold medals and declared him a professional. He would go on to successful careers in pro baseball and football, but the taint on his Olympic achievements stuck with him. It wasn't until 1982, 29 years after his death, that the IOC restored Thorpe's medals.

Fayetteville was also the backdrop for the start and finish of Ruth's illustrious career.

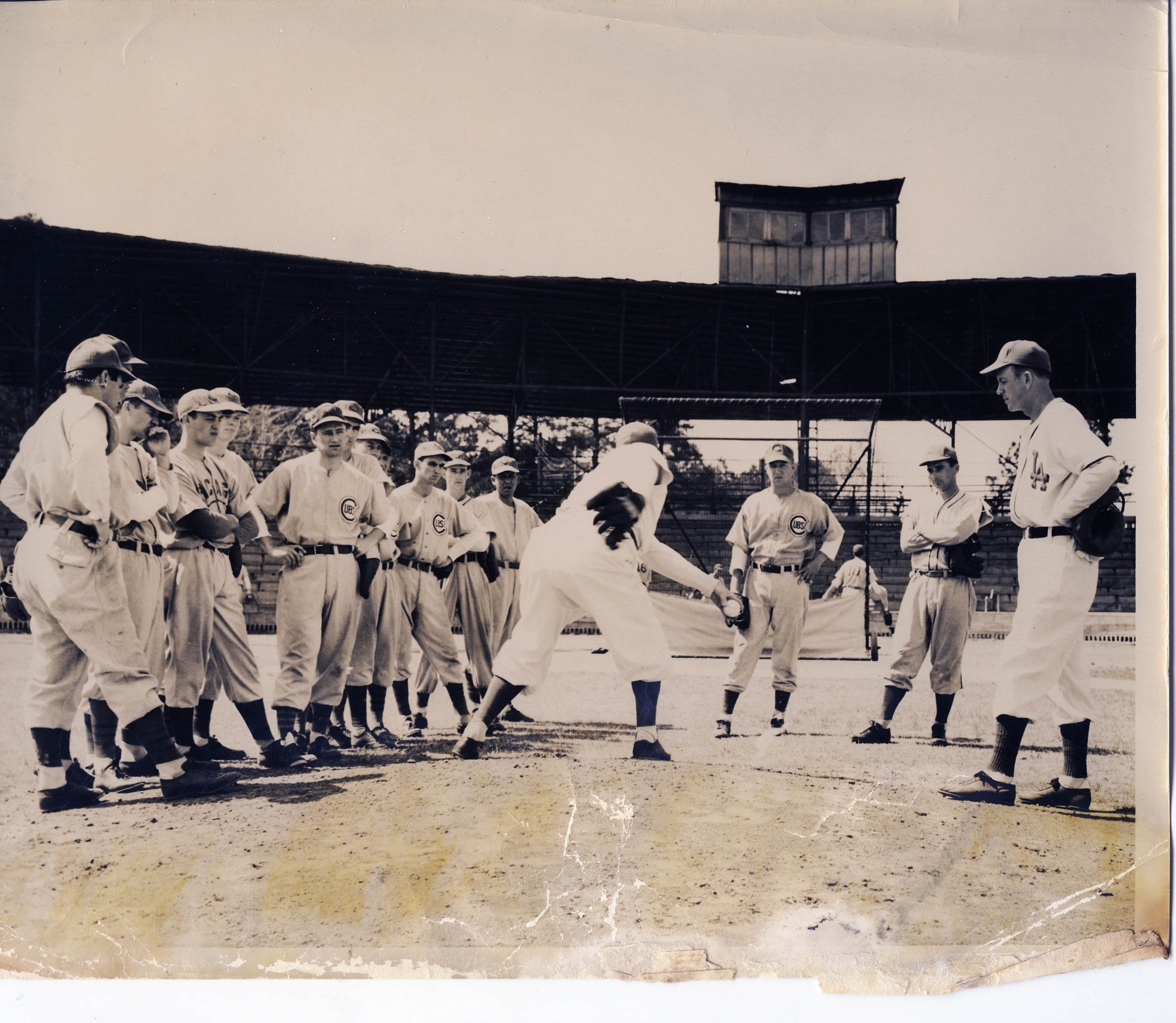

The Baltimore Orioles, then a minor-league club, signed a 19-year-old George Herman Ruth to a professional contract in February 1914 by manager and team owner Jack Dunn. As part of the contract, Dunn agreed to serve as Ruth's legal guardian, a fact that would later contribute to Ruth's fabled nickname. Two weeks after signing, Ruth was taking the first train ride of his life to Fayetteville, where the Orioles had been persuaded to conduct part of the team's spring training by local businessman Hyman Fleishman.

On March 7, Dunn divided his players into two teams for a practice game at the Fair Grounds. In his second time at bat, Ruth launched a home run to right field that landed some 350 to 400 feet away.

“We think of it as his announcement to the world of pro baseball that he was there and ready,'' said Michael Gibbons, director emeritus and historian of the Babe Ruth Birthplace and Museum in Baltimore. “Boom! Off he went. What a way to get going. Only Babe Ruth could have done that. It's a great story.”

Of course, Ruth was not the “Babe” at the time. But that famous moniker undoubtedly was given to Ruth during his stay in Fayetteville.

Whether it was a sportswriter covering the team, or teammates who noticed the special attention paid by manager Dunn, Ruth was eventually referred to as “Jack Dunn's Baby” or “Dunnie's Babe.” By the end of the Orioles' stay in Fayetteville, Baltimore newspapers were using the name Babe Ruth in their reports.

[PHOTOS: Babe Ruth's Fayetteville home run]

A state historic marker at Gillespie Street and Southern Avenue acknowledges Fayetteville's connection to the start of Ruth's history-making career.

Twenty-one years later, Ruth would return to Fayetteville as a 40-year-old legend nearing the end of his career. Having been traded by the New York Yankees in February 1935 to the Boston Braves, he came to town for an exhibition game against N.C. State's college team on April 5. A crowd estimated at 6,700 by The Fayetteville Observer jammed into old Highland Park to witness Ruth walk twice, strike out once and hit into a double play. Afterward, Ruth signed autographs at the Prince Charles Hotel in downtown while the Braves waited for a train to Norfolk, Virginia.

Two months later, Ruth retired with 714 career home runs, which still ranks third on the all-time list.

Jump ahead to the summer of 1969, when one of the most unexpected runs to a World Series title is underway in New York. The Mets, just eight seasons removed from being an expansion team and never having finished above ninth place in the National League standings, suddenly won 100 games and advanced to the World Series against the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles.

Fayetteville-born and Hope Mills-bred right-hander Calvin Koonce won six games and recorded seven saves as reliever during the regular season for the Mets. Due in part to the strong efforts of New York's starting staff, which needed less than six innings of relief help in five games, Koonce didn't appear in the World Series. But he did become the first and only Cumberland County native to win a World Series ring.

Fayetteville is also the birthplace of Archibald Wright “Moonlight” Graham, who appeared in a single major league game as a right-fielder in 1905 for the New York Giants but never got a chance at bat. Graham was popularized in the 1989 movie “Field of Dreams” and was the subject of a 2009 book, “Chasing Moonlight: The True Story of Field of Dreams' Doc Graham,” by former Fayetteville Observer sportswriter Brett Friedlander and UNC Pembroke professor Robert W. Reising.

Fayetteville State University's now defunct baseball program also contributed to the city's professional legacy by helping develop future major league pitcher Jim Bibby in the early 1960s. Bibby, a 6-foot-5 right-hander, left FSU in 1969 for the pro ranks and went on to win 111 games over 12 big-league seasons and a World Series title with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1979. He also hurled the first no hitter in Texas Rangers history in 1973 with a 6-0 blanking of the Oakland A's.

Fort Bragg became the focus of the sports world on July 3, 2016, when Major League Baseball staged its first regular-season game on a military installation. MLB constructed a stadium in just four months on Fort Bragg for the game between the Atlanta Braves and Miami Marlins.

A crowd of 12,582 mostly active-duty soldiers and their families was in attendance as the Marlins scored a 5-2 victory.

“There were a lot of firsts here today,” Braves manager Brian Snitker said at the end of the game. “The whole day was unbelievable from the time we woke up at the hotel until the last out was made. The bad part is we lost. But the good part is this is something I'll remember the rest of my life.”

For Fayetteville, it was just another chapter in a long history with professional baseball.