American-Statesman at 150

Born in the shadow of America’s darkest days to shine a light on Austin

Born in the shadow of America’s darkest days to shine a light on Austin

The small printed words line up in narrow columns.

No images interrupt the sea of gray that spreads over four pages.

A banner across the top of the front page reads: “The Democratic Statesman,” and under that: “Vol. 1. Austin, Texas, Wednesday Evening, July 26, 1871. No. 1.”

The rest of the tightly packed inaugural edition of the newspaper that eventually became the American-Statesman might seem strange to readers today. Yet many elements — local, regional and national news, feature articles, wire stories and a variety of advertisements — would look somewhat familiar.

That first edition, however, contained a core political message — inherently racist in content — that would appear distinctly alien in a mainstream American daily newspaper today. Over the next 150 years, this newspaper would change as frequently and as drastically as the city it was founded to serve.

In 1871, although Austin had served as capital of the Republic of Texas and then of the state for most of the past 32 years, it was still something of an emerging frontier town of some 4,500 people. Streets were not paved and public displays of violence were not infrequent.

Comanches still raided across the plains to the west.

Government and politics generated the most business. The University of Texas and other colleges had not yet opened.

The 1854 state Capitol looked more like a county courthouse. And while Congress Avenue bustled with business, the first railroad — which brought rapid economic growth and a sense of contact with rest of the country — would not arrive until later in 1871.

The original Statesman offices stood on Congress Avenue between Hickory and Ash (now Eighth and Ninth streets).

American-Statesman at 150

The first edition of what would become the Austin American-Statesman was published 149 years ago today. Over the next year leading to our sesquicentennial, we will periodically look back at the newspaper’s history and its role in Austin’s rise. Follow our journey on Twitter and Facebook, where we will share a front page from our archive each day over the next year.

Inside the Statesman’s very first edition

The first four-page issue of the Democratic Statesman came out July 26, 1871. [Contributed by Newspapers.com]

In issue No. 1, five columns divide each of the four broadsheet pages, a customary format for the times.

Among those columns is the release of a long political manifesto that jumps to multiple pages, as well as a prominent box on Page 1 listing the members of the Central and Senatorial Executive Committee chosen by the State Democratic Convention.

From its founding, the Democratic Statesman was expressly the house organ of the Texas Democratic Party. And issue No. 1 contains the convention’s report.

The manifesto, written in trumpeting prose, lays out the positions of the party during the complicated period of Reconstruction, which followed the Civil War. There is much talk of the U.S. Constitution, states’ rights, taxation, liberty and, especially, “Democracy,” as well as party unity and support for the platform adopted at the convention.

The Statesman was, in fact, the only major Democratic newspaper in the state at a time when the Democrats sought to regain power.

At the core of the document is a call to undo the effects of military rule and so-called “Radical Reconstruction,” the third major phase of change during the nine years after the Civil War, as states in the defeated South moved toward self-rule.

READ: Bridges: Denouncing the views of our founders

During the short transition phase starting in 1865, Texas was occupied by Union troops as the tattered remnants of the Confederate military, the freed slaves, some of them resettled in independent freedom colonies and others attempted merely to survive. The interior of Texas had not been the site of any major Civil War battles, but it was economically ravaged.

The military remained, but the second phase, the “Presidential Reconstruction,” allowed some of the former white leaders to resume power with an appointed governor. This led to a very conservative state government at odds with the aims of the national government, especially in regards to the rights of African Americans.

The third phase was the “Congressional Reconstruction,” which was considered radical because it included the active political participation of African Americans and their allies in the Republican Party.

Democrats hoped to reinstate white supremacy in Texas and to oppose the Republicans, who promoted the well-being of African Americans, including the right to vote and be elected to office. The U.S. military enforced those voting rights.

“The present issue of the Democratic Statesman is distributed in order to apprise the Democrats, and all others opposed to the continuance in Texas of the present Radical rule,” one part of the manifesto reads. It later continues: “We call upon all who may feel an interest in the subject, to send in the subscriptions without delay.”

While the state Democratic platform acknowledged “that the abolition of slavery as a result of war is accepted as fixed fact,” it also resolved “that the immigration of the white race, from all quarters of the world be encouraged.”

It was effective. The Statesman is credited with playing a major role in the 1873 election, which brought down the state’s Republican regime and brought back the conservative Democrats.

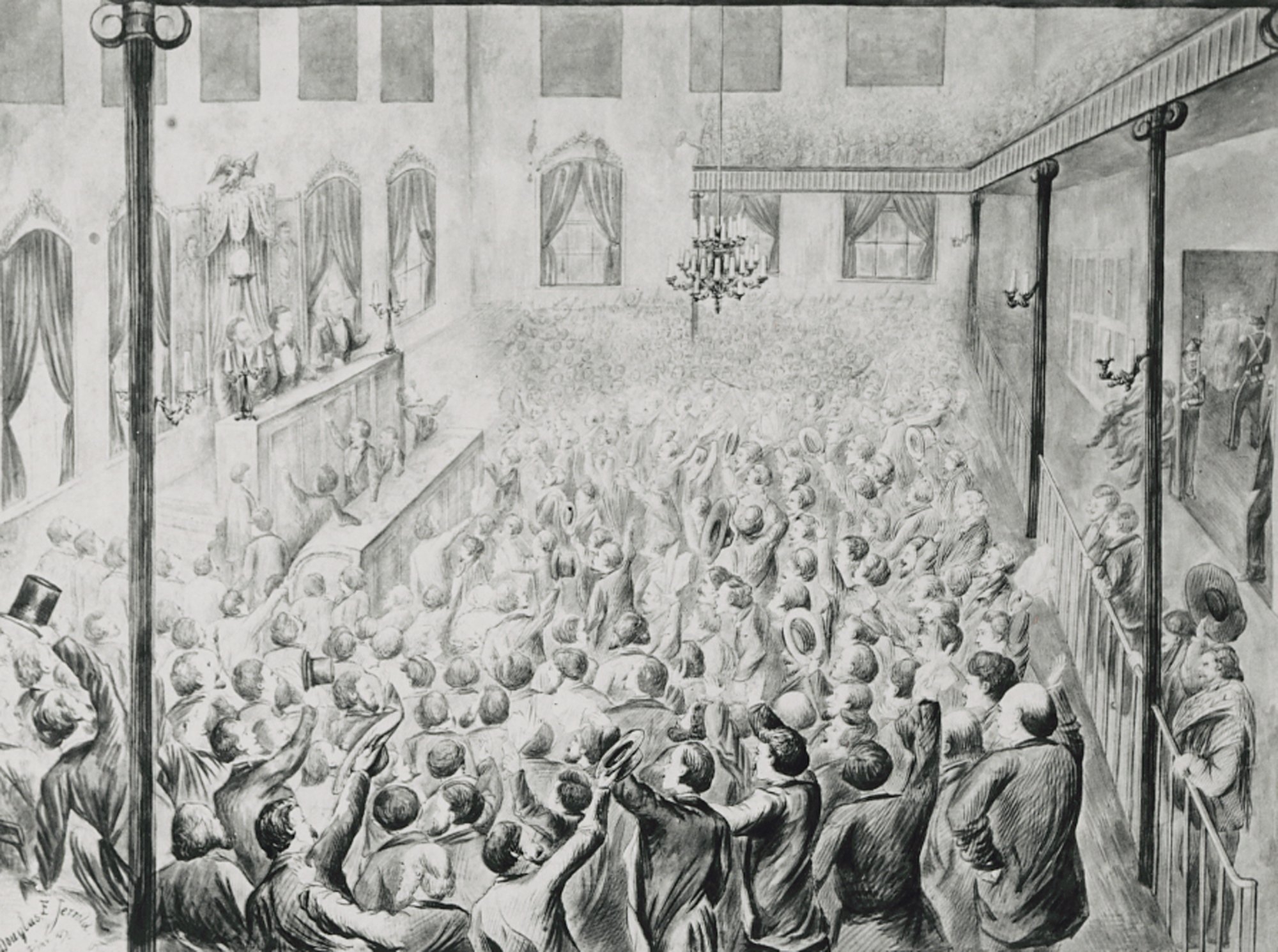

A drawing of the contentious inauguration of conservative Democrat Richard Coke in 1874, which followed a famous court case and signaled the end of Reconstruction. [Austin History Center/ Austin Public Library, PICA]

In 19th century, parties’ roles were reversed

What else did the “Democratic” in the newspaper’s name suggest to readers of the day?

“It was the party of slavery and secession — with a few prominent members, such as Sam Houston, opposed to secession — hence the rhetoric,” said Don Carleton, director of the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas. “The year that the Statesman began, 1871, was noteworthy because it was the year that the Texas Republican Party began to lose state elections to the Democrats, which began a two-year decline that led to the defeat of Republican Edmund J. Davis — a Texan who opposed secession, joined the Union Army, and fought against the Confederacy — by Democrat Richard Coke in 1873.”

Davis at first refused to give up his office, but he failed to receive the support he had requested from the federal government and was forced to vacate the governorship, Carleton pointed out. Coke’s election, combined with the compromise that awarded Rutherford Hayes the presidency in 1876, led to the end of Reconstruction in Texas and across the South.

“Austin, simply because it was the state capital, was at the center of all the numerous political and governmental controversies during Reconstruction,” Carleton said. “The Statesman actively supported the Democrats’ political insurgency and the fight to end Reconstruction, which was not the corrupt and evil administration that supporters of the ‘Lost Cause’ claim it was.”

The Statesman actively supported the Democrats’ political insurgency and the fight to end Reconstruction.

Just how effective were the Statesman’s anti-Reconstruction efforts?

“That’s very difficult to determine,” Carleton said. “However, we have to understand that newspapers were much more influential in the late 19th century and through most of the 20th century than they are today, so we can reasonably assume it had an impact to some degree. It’s just impossible to measure how much, especially from this distance in time.”

A great irony of this history is the complete reversal of positions taken by the Democrats and the Republicans that began during the New Deal and culminated with Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy,” which began the move of conservative Southern Democrats into the Republican Party.

Walter Buenger, a professor of Texas history at the University of Texas and chief historian of the Texas State Historical Association, said that being a Texas Democrat in 1871 could mean multiple things.

“There are those who are sometimes called Bourbon Democrats or called Redeemers,” Buenger said. The Bourbons were a conservative, pro-business faction, and the Redeemers strove to regain power and enforce white supremacy. “And then there were more moderate Democrats, who drifted back and forth between supporting Democrats and moderate Republicans and independents.”

Most Democrats opposed giving the vote to African Americans or paying for public education that would lift up African Americans.

“Redeemer Democrats were very much interested in as limited a government as you possibly could get by with,” Buenger said. “Imagine the Tea Party of today and call them Democrats and you’d have an image of what these people were. They wanted limited government, white supremacy and partisan control.”

Taxation came freighted with racial meaning.

“Taxes were used by Republicans to finance public education for anyone including African Americans, among other things,” Buenger said. “So much of it boiled down to race and partisanship.”

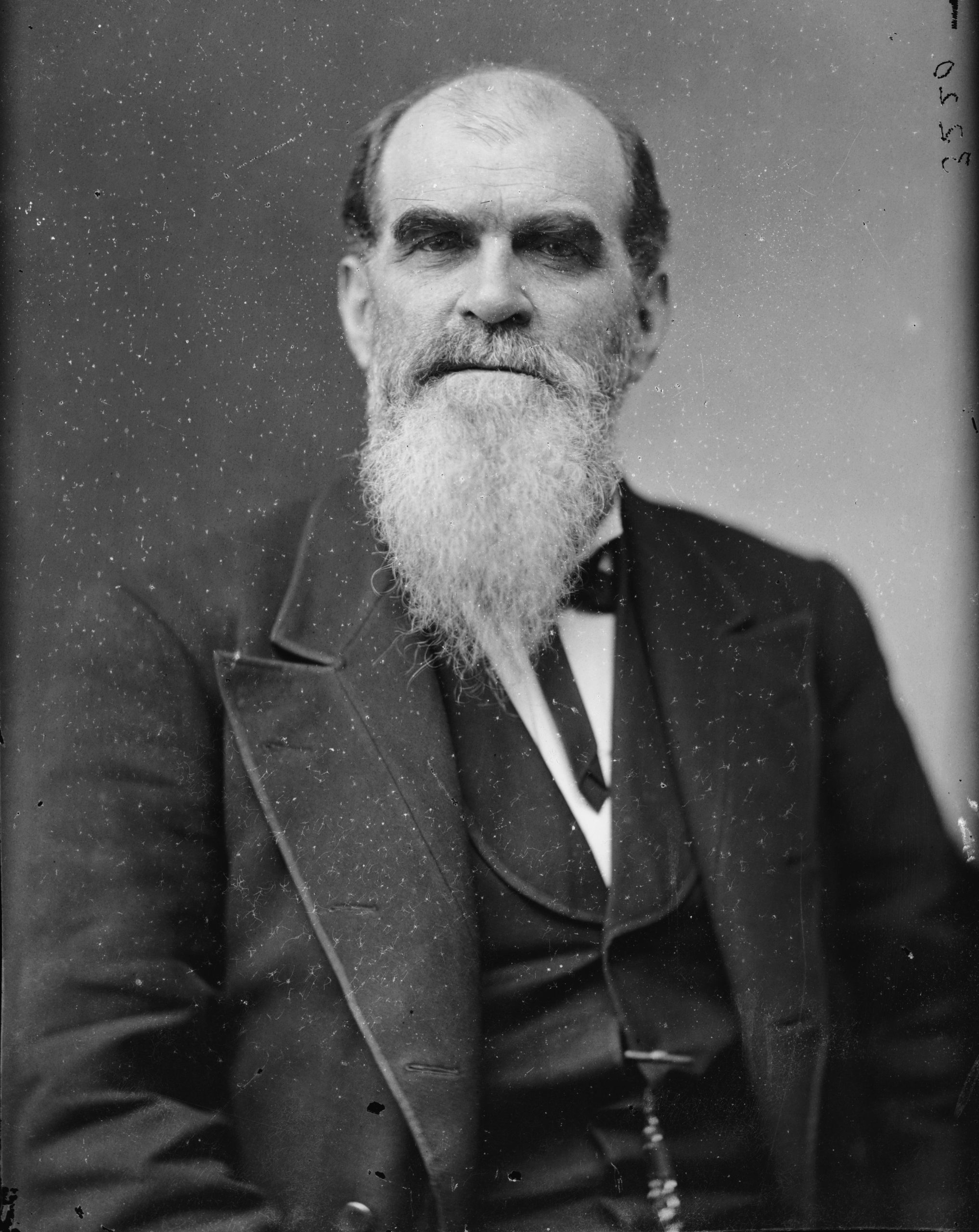

The Democratic Statesman helped elect Democrat Richard Coke as Texas governor in 1874. [Contributed]

For a short period after the Civil War and before Radical Reconstruction, Texas elected a very conservative government that passed Black codes, restrictive laws designed to limit the freedom of African Americans, similar to ones enacted before the war.

“They tried as best as possible to make African Americans slaves in everything but name,” Buenger said. “Race remained the major theme of Texas politics into the early part of the 21st century.”

It was during this period, too, that Lost Cause adherents attempted to rewrite American history — and pretty well succeeded in the eyes of many Southerners.

PHOTOS: The American-Statesman made news at 15 or more spots

“They took an eraser to history,: Slavery wasn’t all that important. We just wanted to get these Carpetbaggers and Yankees who were so corrupt out of government,” Buenger said. “They simply erased the central role of African Americans.”

The newspaper reinforced this viewpoint. Only a couple of words published in issue No. 1 refer directly to African Americans.

“This paper would have been dedicated to returning Texas to as close as possible to January 1860,” Buenger said. “The same landed elites who had controlled Texas before the war came back to power with these Redeemer Democrats, as well as a class system of white supremacy.”

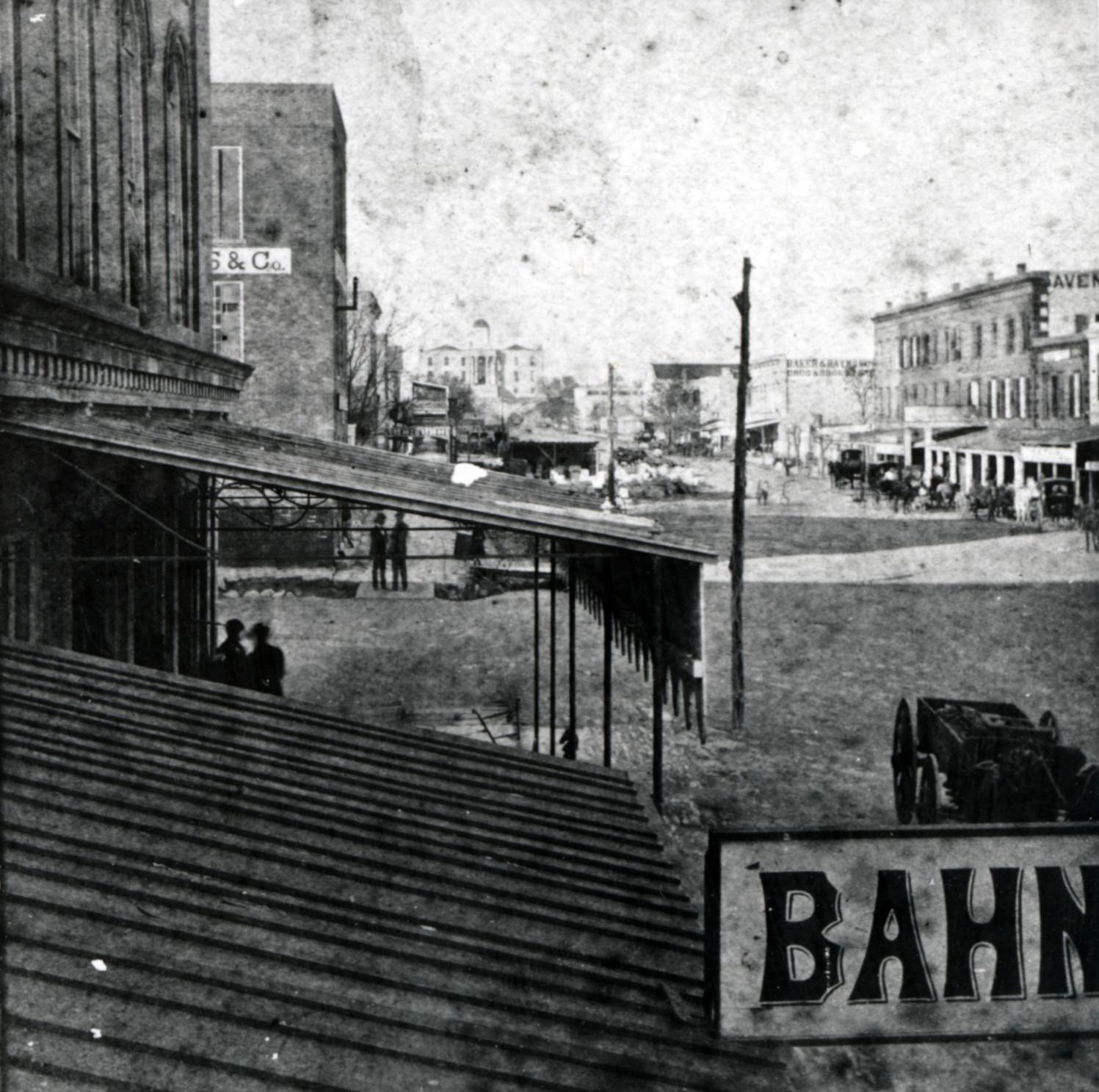

When the Daily Statesman debuted in 1871, it focuses much of its reporting energies on state government, including what happened at Austin’s second Capitol. Built in 1853, it looked more like a nice-sized county courthouse than the main government building for a state the size of Texas. [CONTRIBUTED BY AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER PICA 06175]

Origins of newspapers in Austin

The Democratic Statesman, which went daily in 1873 and raised its rates to $12 a year, was not Austin’s first newspaper. According to the authoritative Handbook of Texas, at least 10 newspapers were published in Austin during the period of the Republic of Texas alone.

The Austin City Gazette appeared on Oct. 30, 1839, during the city’s first year. A weekly, it had a subscription price of $5 a year. Like the early Statesman, it was dominated by the proceedings of the legislature. The Gazette paused publication in March 1842 over fears of a Mexican invasion. It survived through Aug. 17, 1842, and was replaced by the Austin Western Advocate.

The Austin Texas Sentinel — sometimes spelled differently — challenged the Gazette for readers from 1840 to 1841. One of its publishers was George W. Bonnell, a journalist and soldier that some believe is the namesake of Mount Bonnell. After 1841, the Sentinel was split into the Daily Texian and the Weekly Texian.

Another early challenger was the Austin Rambler, which lasted only four or five issues.

The Gazette for June 10, 1840, mentions the Austin Six-Pounder, which could have been yet another newspaper, or perhaps the Gazette’s nickname for a rival paper. The same explanation is possible for something called the Austin Spy, which was associated with the humor of Dr. Richard F. Brenham, who fought in the Texas Revolution, practiced medicine and posthumously became the namesake of the town in Washington County.

The Austin Anti-Quaker appears to have been published to oppose peaceful relations with Mexico in 1842.

READ: Meet the woman who’s read the Austin American-Statesman since 1939

At first, the Austin New Era was a journal of the Convention of 1845 while Texas was becoming a state, thus the name.

It was the Austin State Gazette that dominated the scene from the pre-Civil War days until Reconstruction. Published by William H. Cushney, it started on Aug. 25, 1849. The State Gazette took strident states’ rights positions, and it tangled with Sam Houston in the erratic times before secession, which Houston as governor opposed.

The State Gazette called for reopening the slave trade with Africa, and it blamed the North for problems with slavery, because of its resistance to enforcing fugitive slave laws. John F. Marshall, who bought the State Gazette in 1854, became its most famous editor. He devoted a flood of columns to slavery, sectionalism and politics in general.

Its main opponent was the Texas State Times, which supported Houston and Unionist candidates.

When Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, the State Gazette demanded that Houston bring the legislature into session and secede. At the state’s Secession Convention, Houston would not take the oath of loyalty to the Confederate States of America, and so the convention removed him from office.

Despite the newspaper’s influence, Travis and Williamson counties voted against secession.

Downtown Austin looked a bit like the set of “Deadwood” when the Democratic Statesman debuted in 1871. [CONTRIBUTED BY AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER PICA 02437-C]

In a class of its own

That left the field open to the earliest predecessor to the Austin American-Statesman. The Democratic Statesman grew in size and complexity, but for its first decade the paper did not stray far from the cause of reestablishing the Texas Democratic Party and all that would come with its return to power.

On July 15, 1880, the Democratic Statesman became the Daily Statesman, the first of several name changes over the decades. Underneath the new name ran the line: “The Only Democratic Paper Published in the Capital of the State of Texas.”

During the intervening years, its offices had moved to Ninth and Congress, then 10th and Congress.

Six pages long, with occasional illustrations that broke up the text, it was no longer an activist insurgent. The Statesman had become the establishment paper. Democratic candidates had been elected up and down the ballot during the 1870s, so the Daily Statesman not only changed its name but shifted its rhetoric.

It had come a long way from being an internal organ of the Texas Democratic Party. The Statesman still supported Democratic candidates — and therefore the Jim Crow segregation laws that multiplied during the 1880s — but publishers John Cardwell and a man identified only as Mr. Morris clearly wanted to appeal to a wider readership. No longer did the paper run pages-long news articles or manifestos about the party and its values.

Advertising boomed. And the paper regularly published items that would seem odd in a modern newspaper, such as railroad timetables, lists of residents who were delinquent on their taxes and something called the “Twenty-Five Cent Column,” a direct forerunner of classified ads.

Although there have always been competitors, descendants of this Daily Statesman have remained the dominant media outlets in Austin ever since.

A relatively short editorial published on the 1880 name-change day, titled “The Statesman and Its Politics,” summed up the changes: “The Statesman, emblematical of the new era that dawns on Democracy, presents itself this morning, relieved of its old dress and clothed in a new one.”