THEIR STORIES

Students who learn two languages

are ahead of the game

Barbieri Elementary School first opened a few dual-language classrooms in 1990, joining just a handful in the nation at the time. All classrooms transitioned to dual-language in the late 1990s, and it remains the district’s only dual-language school today. Alumni of the program look back on their experience and how it shaped their lives.

Part of a secret club

When her family settled in Framingham, Maria Gomez had a rule for her children: Always speak Spanish at home.

They fled Ecuador in the early 1990s, restarting their lives in the suburb west of Boston. Enrolling the children in dual-language classes was an essential way to hold onto a piece of home, said Gomez.

“Nothing in the world is more important than your heritage. The language, the knowledge, the love — no one can take it away from you,” said Gomez, sipping coffee in her Saxonville apartment. “I would do everything in my power to make sure they could speak Spanish.”

Cynthia Gomez, a first lieutenant with the Massachusetts National Guard, laughs with her mother, Maria, over coffee, March 6, 2020. Ann Ringwood | MetroWest Daily News Staff

Her son was first to win a spot in the Barbieri Elementary School’s program through a lottery. Because of sibling privilege, her daughter, Cynthia, was automatically enrolled, joining the 6-year-old program in 1996.

The school remains the district’s only all dual-language school. Attending classes at Barbieri, Cynthia Gomez, now 29, remembers feeling like she was a member of a secret club.

“As a kid, you knew you were different but you never understood what exactly it is. You can’t pinpoint exactly what makes you different, but for me and my friends it felt like we were part of a club that could speak Spanish,” she said.

Cynthia Gomez, right, at her Framingham High School graduation in 2009, with Alma Garcia, left, and Esta Montano, Gomez’s mentor. Courtesy Photo |

Massachusetts National Guard 1st Lt. Cynthia Gomez visited with her parents, Maria and Omar, in Framingham in March. Ann Ringwood | MetroWest Daily News Staff

Cynthia Gomez talks with her father, Omar, after he returned home from doing errands, March 6, 2020. Ann Ringwood | MetroWest Daily News Staff

As fairly new immigrants, Cynthia Gomez said the program also made her family feel at home, seeing Spanish signs in the classroom and hearing the language in the halls. Maria Gomez estimates she was at the school three times a week to volunteer in the classroom. It’s not uncommon for her to be recognized by former students around the city today.

“It was welcoming, as opposed to separating them even more,” said Cynthia Gomez.

Cynthia continued with the two-way program through high school, graduating in 2009. She went on to Smith College in Northampton, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in economics and global development.

Today, Cynthia Gomez works in the Department of Economics at Harvard University as a faculty assistant, as well as serving as a first lieutenant in the Massachusetts National Guard’s logistics unit in Springfield. She leans on her fluency in Spanish daily, especially while interacting with the Latino-heavy population in Springfield.

More importantly, though, she points to some of the stronger relationships in her life as a product of the program. As an undergraduate, she was able to study abroad in Spain. While abroad, she met her fiancé.

“It completely changed my life and I think it really started in kindergarten,” said Cynthia Gomez.

‘I don’t have to translate the words in my head’

When her Moroccan father and American mother were flooded in words they did not understand, 13-year-old Aliya Benabderrazak moved to help.

In 2014, her family picked up everything and moved from Framingham to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. She and her siblings — who all attended Barbieri’s dual-language program — played translator for their parents, often critiquing one another’s efforts.

Aliya Benabderrazak (center), at a football game with Barbieri Elementary School friends Hannah (right) and Chloe (left) Pearce. The three girls attended the dual-language program together.

Aliya Benabderrazak poses for a photo in a Barbieri Elementary School classroom. Courtesy Photos |

“I would translate something one way and my sister would correct me or my brother would translate and I would correct him,” said Benabderrazak, now 18. “It was kind of weird, but I guess it made us all feel needed and useful and helpful to our parents.”

Benabderrazak’s mother, Lori Greene, said the abrupt move came after the family visited the city on vacation. She was burned out by life in the U.S. and said “something (about that trip) made me realize there was another option besides just over-scheduled craziness.”

The original plan was to live there for one year, but within five weeks they “did not want to go back.”

“It was me, it was my stress levels that led us here,” said Greene. “Aliya was really not on board but grew to love it.”

Benabderrazak had completed fifth grade in Barbieri and briefly attended McAuliffe Charter School before the move. With a strong grasp on academic Spanish, it was at first a struggle to adjust to a more conversational, social version.

“She was a tiny bit challenged at the beginning — ‘How do I become friends with someone in Spanish? How do I talk with the girls on my soccer team or my neighbors or the guy down the street?’” said Greene.

Aliya Benabderrazak, now a student at University of Tennesse Knoxville. Courtesy Photo |

Today, Benabderrazak can seamlessly switch from English to Spanish and hopes to add Arabic to her skill set. Her journey to fluency in Spanish started in 2007, when she was an overwhelmed Barbieri kindergartner. She remembers she could not speak English unless she wore a “special necklace.”

“My mom always told me that I was really worried that I wouldn’t know how to ask to go to the bathroom or something that I needed to know,” said Benabderrazak.

But she never felt defeated when she grappled with Spanish.

“I was really learning Spanish as I was learning English. It was kind of a struggle in both languages and it wasn’t necessarily, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s so hard to learn how to read in Spanish,’ because I didn’t know how to read at all,” said Benabderrazak.

When the professor speaks to me, I don’t have to translate the words in my head. I just understand what he’s saying.

Within a few months, Benabderrazak felt comfortable enough with the language to speak it at home. At times, she even spoke Spanish in her sleep.

Today, she is studying psychology at the University of Tennessee Knoxville, while pursuing a minor in Spanish. She hopes to work with children with mental illnesses.

“When the professor speaks to me, I don’t have to translate the words in my head. I just understand what he’s saying,” said Benabderrazak.

‘I can connect with people’

Twins Hannah and Chloe Pearce have been able to forge unexpected ties with people across the city due to their fluency in Spanish.

For Hannah, it allows her to converse with her Colombian boss while working at Saxonville Mills Café & Roastery. Chloe was able to step in and translate for non-English-speaking students in gym class. The two, who are members of the Class of 2020 at Framingham High, could also transfer their Spanish skills into Portuguese to speak to Brazilian students at the high school.

“It’s just been so cool that I can connect with people that some of my friends can’t,” said Chloe, 17.

Framingham High School twin sisters Chloe, left, and Hannah Pearce in their Framingham home. Ken McGagh | MetroWest Daily News Staff

It can help newcomers feel more welcome at the school when fellow classmates speak their language, said Hannah.

“For some of these kids, it’s just them … and if you don’t speak the same language, it can create a divide in the school. There is nothing to lose if more people know more languages,” said Hannah, 17.

The two attended Barbieri’s dual-language program, before taking a brief absence from the program while attending McAuliffe. They re-entered the program at the high school, where classes felt “basically like an advanced English class but in Spanish,” said Hannah.

Framingham High School senior Chloe Pearce, 17, practices with her fellow girls varsity baskeball teammates in Feb. 2020. Ann Ringwood | MetroWest Daily News Staff

Framingham High School Class of 2020 graduates Chloe, left, and Hannah Pearce. Ken McGagh | MetroWest Daily News Staff

Hannah Pearce, at work at Saxonville Mills Cafe in February. Hannah and her twin Chloe both went through the Barbieri School dual language program, and are fluent in Spanish. Art Illman | MetroWest Daily News Staff

They read books such as the nearly 1,000-page “Don Quixote de la Mancha” (“The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha”) and the novella “Crónica de una muerte anunciada” (“Chronicle of a Death Foretold”) in Spanish.

It’s powerful to be able to read the words an author intended for readers to see rather than a watered-down translation, said Hannah.

“When you see stuff that’s translated and you know what the original was, you can tell if there was something lost there,” she said.

An opportunity for a step ahead

As immigrants from Trinidad and Tobago, Barbieri’s dual-language program was at the top of the list for Reyad Shah’s parents.

“Having the ability for their son to pick up another language free while at school was something they couldn’t have imagined for themselves. My parents saw it as a real opportunity to give me a step ahead,” said Shah, now 30.

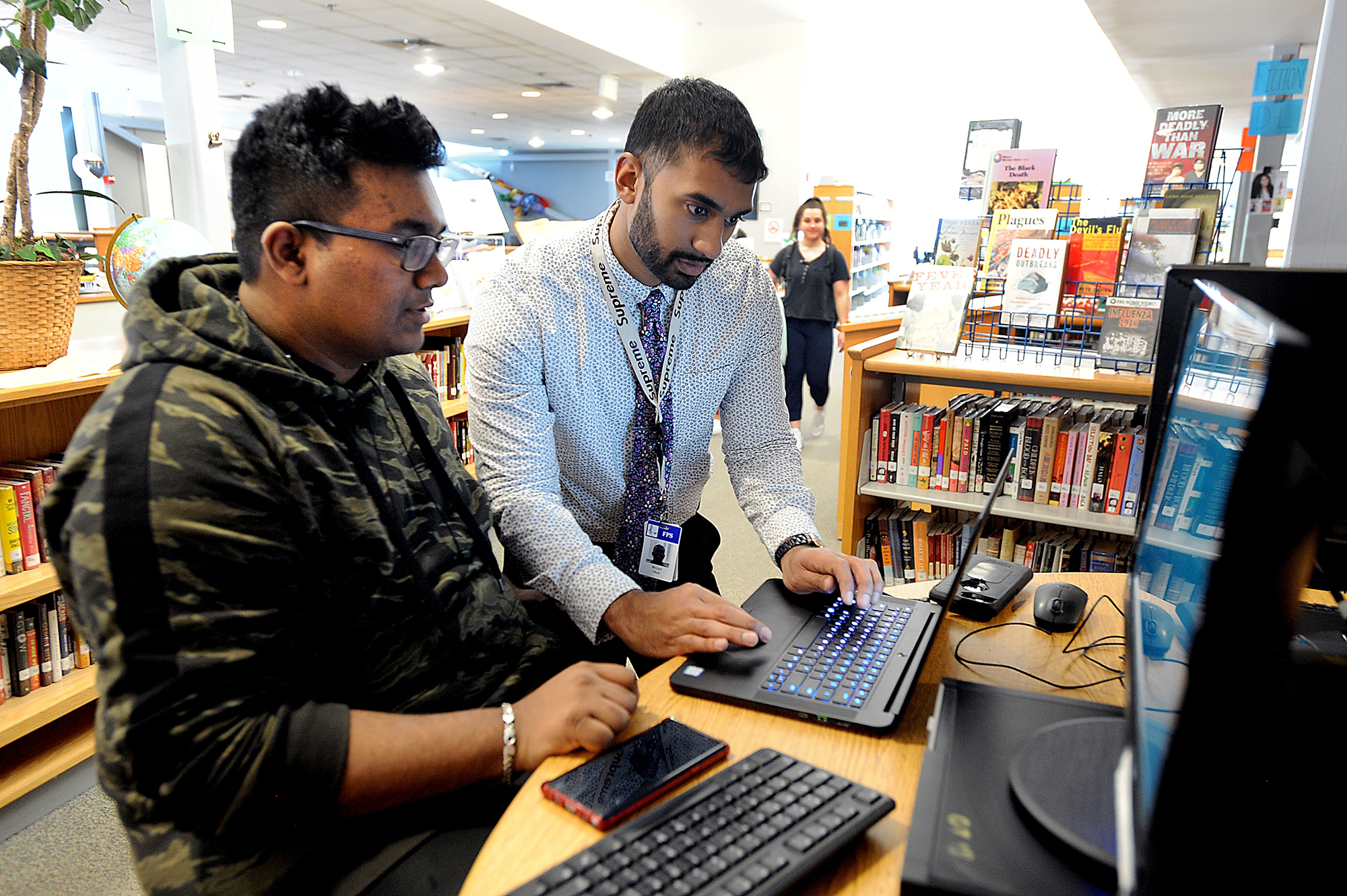

Reyad Shah, Out of School Time Coordinator at Framingham High School, right, with junior Mohammed Khan in the library. Khan was working on a website for the student led alumni office. Art Illman | MetroWest Daily News Staff

Reyad Shah poses with his classmates at his 5th grade graduation. Courtesy Photo |

He started at Barbieri in 1995, when the program was still in its infancy. District officials had rolled out the learning method in 1990 with the 50/50 model, meaning students spent half their day learning in Spanish and the rest in English. During its first years, the program was just practiced in a few classrooms before it was expanded to the entire school.

Shah remembers having lessons in a makeshift classroom in the library. Teachers had assembled dividers to create the space, working to accommodate the small but growing program at the school.

“It was like, ‘We have all these kids who want to access this program. How do we accommodate that? We have to make a classroom,’” said Shah.

Today, he regularly uses Spanish in his role as an out-of-school coordinator at the high school. Sometimes, students have missed the bus and are not sure how to get home. Other times, they’re looking for directions to a classroom.

“Kids will stand there and stand there, waiting for someone to make that connection that they don’t speak English,” said Shah.

Zane Razzaq is the multimedia journalist who covers education and the city of Framingham for the Daily News. She earned her masters of arts in journalism from Northeastern University and her bachelor’s degree from Smith College. After working for a year at The Patriot Ledger, she joined the Daily News in April 2018. She can be contacted at

Zane Razzaq is the multimedia journalist who covers education and the city of Framingham for the Daily News. She earned her masters of arts in journalism from Northeastern University and her bachelor’s degree from Smith College. After working for a year at The Patriot Ledger, she joined the Daily News in April 2018. She can be contacted at