We’ve only just begun

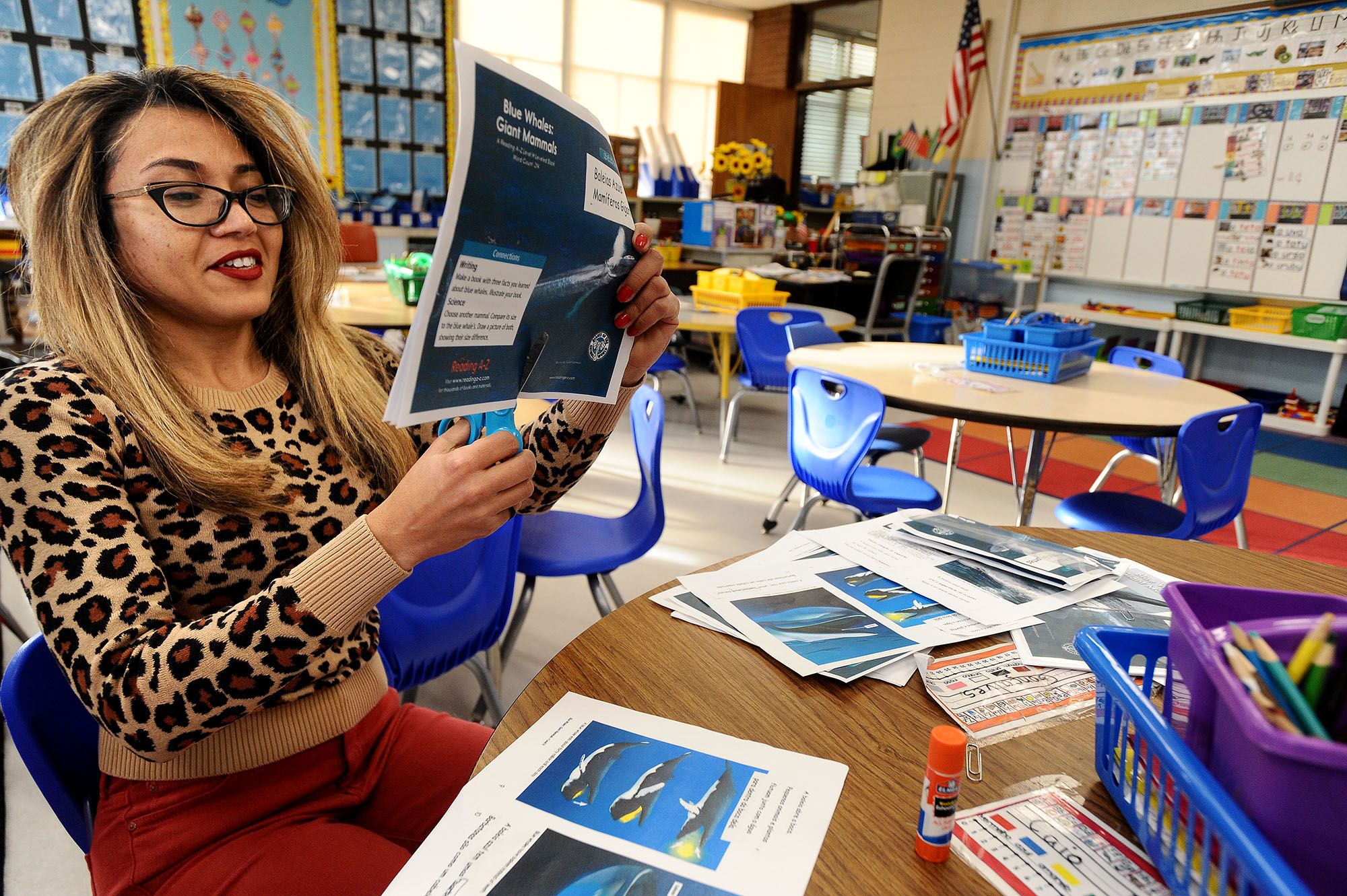

At the Potter Road School, first grade teacher Josefa Carvalho pastes Portuguese subtitles over English words and then copies and staples the pages into books for the students. Teachers in the dual-language program often have to create their own material because of a lack of appropriate Portuguese materials. Art Illman | MetroWest Daily News Staff

The hurdles are many for teachers of Framingham programs

In an empty classroom at Potter Road Elementary School, first-grade teacher Josefa Carvalho was hard at work.

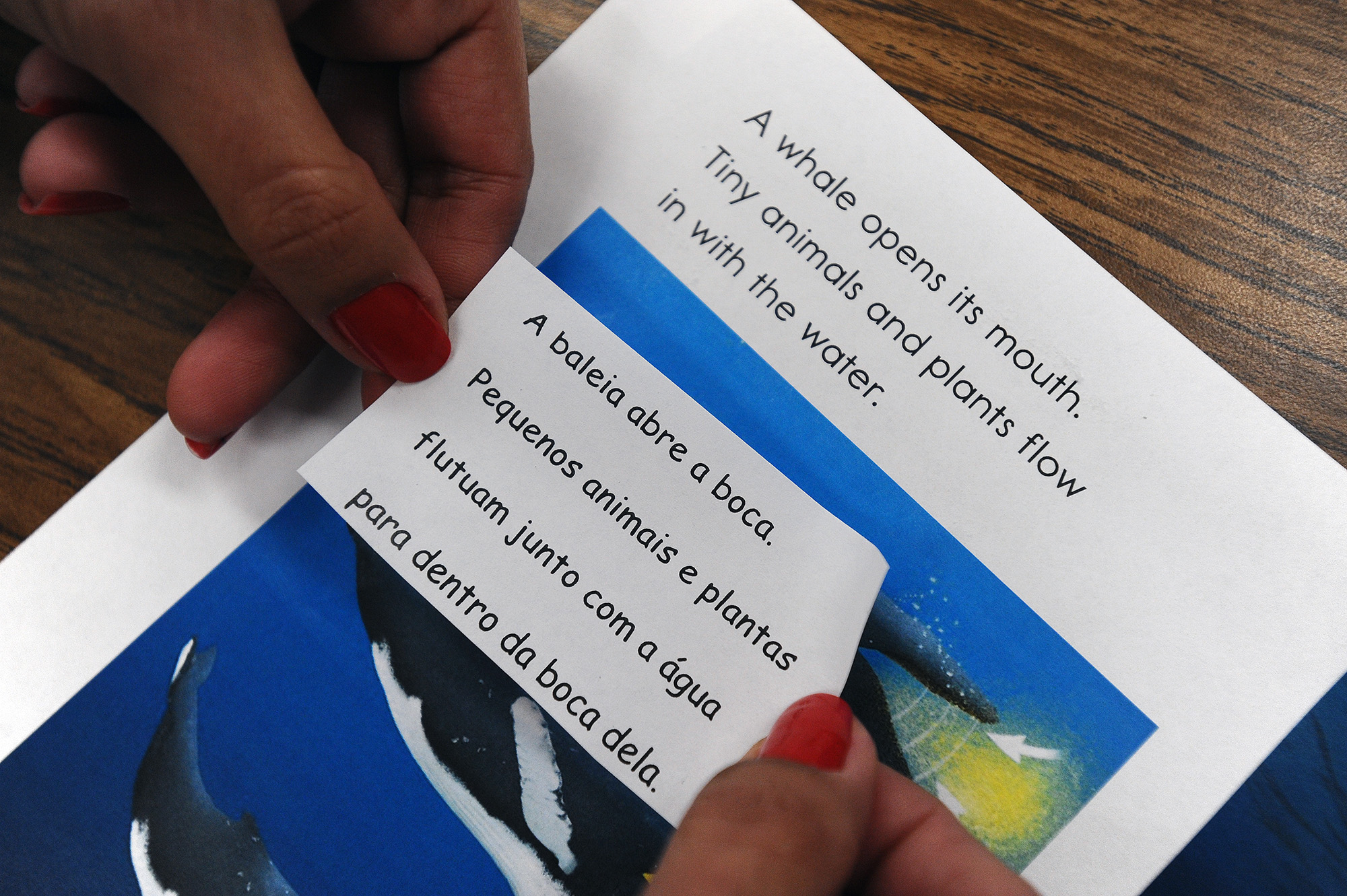

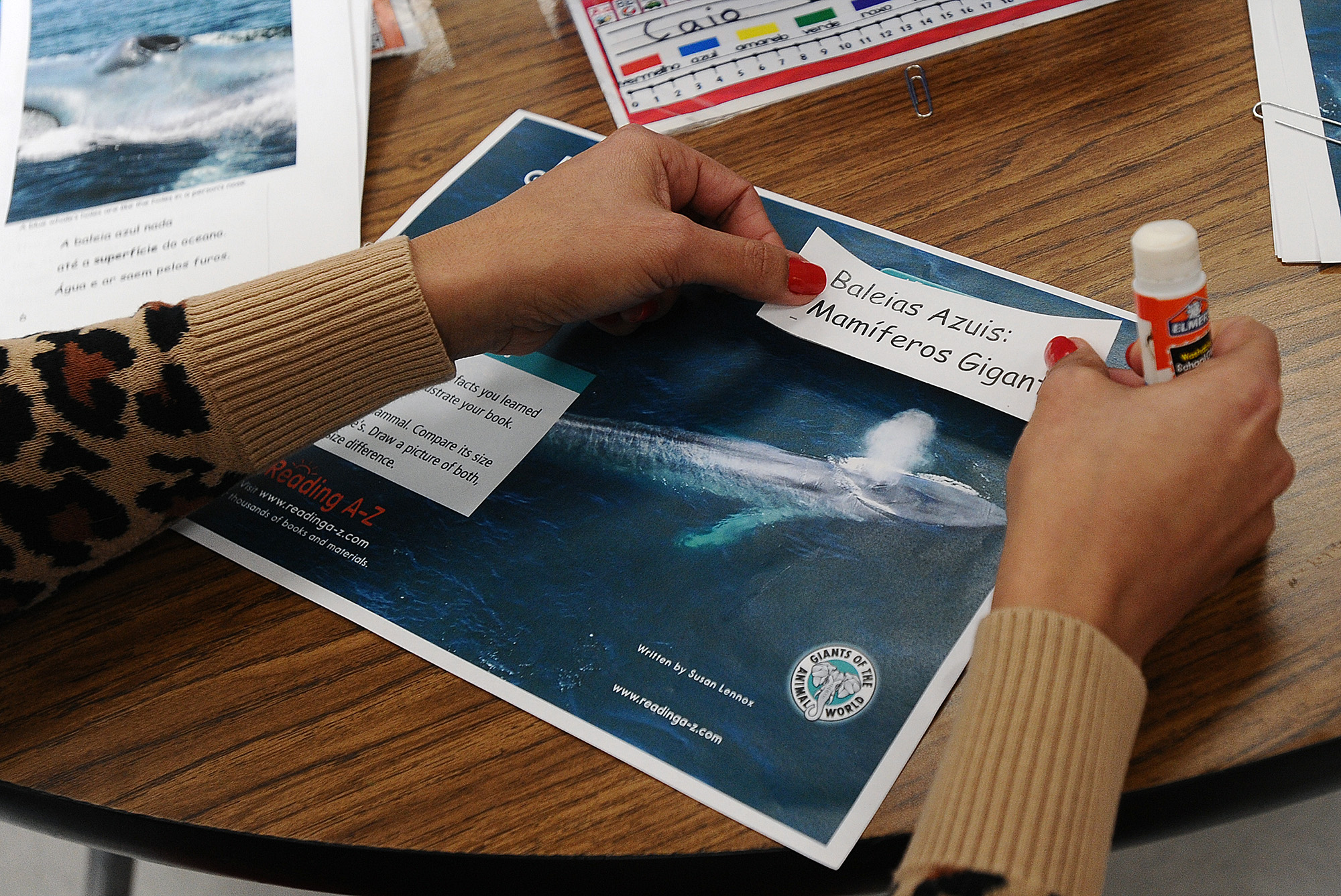

She’d already painstakingly gone through the pages of a children’s book to translate and type up each line in Portuguese. Later, she waited for the printer to spit out sheets of paper and then cut each sentence out. Next was pasting the newly converted lines over the original English that filled the book.

In about an hour, “Blue Whales: Giant Mammals” became “Baleias Azuis: Mamíferos Gigantes,” and she had a new book for her students to read in class.

“It really adds up,” said Carvalho on the routine.

Like many teachers who work in dual-language programs, Carvalho grapples with a lack of ready-made materials in her language of instruction and puts in extra time to fill the gap. It’s among the growing pains Framingham and other school districts run up against as they expand or launch dual-language programs.

Principal Lawrence Wolpe praised teachers such as Carvalho as “creative educators who are willing to go that extra mile,” but called it a short-term solution.

“Longer-term is challenging,” he said. “It’s tough to find vendors who will sell texts in Portuguese … you can go to Amazon and you might be able to find a dozen texts, and three of them are appropriate. And maybe we already have those ones.”

And even if they do find children’s books in Portuguese, they’re usually more expensive than those in English or Spanish. A copy of “Horton Hears a Who!” by Dr. Seuss sells for $8.53 on Amazon, but the Portuguese “Horton Choca o Ovo” goes for $36.97.

The same book in Spanish is priced at $11.84.

At the Potter Road School, first-grade teacher Josefa Carvalho pastes Portuguese subtitles over English words and then copies and staples the pages into books for the students. Art Illman | MetroWest Daily News Staff

First-grade teacher Josefa Carvalho pastes Portuguese subtitles over English words and staples the pages into books for her students at the Potter Road Elementary School. Art Illman | MetroWest Daily News Staff

It’s a problem district leaders face when they launch dual-language programs in less common languages. Until recently, most initiatives were in Spanish-English, leaving a lack of appropriate curriculum and materials in Portuguese.

A possible solution is for staff members to purchase the books while abroad and be reimbursed later, but that would be straying from the district’s normal process of working through reputable vendors to buy books, said Superintendent of Schools Robert Tremblay.

For example, it’s unclear what the reimbursement process would be if a teacher paid with cash for a book in a Brazilian market or bookstore.

“It’s much more difficult to be accounted for in that model,” said Tremblay. “But if we can’t get books through a local vendor, that might be the only way we can get authentic literature in our classrooms. So that’s what we’re trying to figure out.”

The problem has only intensified with the COVID-19 outbreak, as there’s also a lack of appropriate digital resources. District leaders have begun to build a library of remote resources, including videos of teachers reading aloud and websites where students can explore lists of vocabulary words.

A multi-lingual bulletin board in the main office greets visitors to the Potter Road Elementary School in Framingham. [Daily News and Wicked Local Staff Photo/Art Illman] Art Illman | MetroWest Daily News Staff

Lost generation of teachers

A shortage of bilingual teachers has also posed a challenge for districts looking to launch or expand dual-language programs. As Potter Road prepared to expand its dual-language program to third grade this fall, Wolpe held several virtual interviews with candidates in Brazil.

“Obviously, you don’t want to hire someone because they can speak the language. You want to hire someone because they can speak the language and they’re a good teacher,” said Wolpe.

Experts link the slowness of this specialized teacher pipeline back to the 2002 voter initiative that banned bilingual education in Massachusetts.

In the aftermath of the law, most bilingual transitional initiatives in the state were quickly dismantled and transformed into English-only programs. Dual-language programs that already existed were able to survive, but there were only about 13 at the time.

Framingham and a handful of other districts were notable exceptions, as they navigated a time-consuming process of getting waivers from the law to continue practicing bilingual education.

“The effect was pretty profound,” said Patrick Proctor, a Boston College education professor. “Bilingual education as a practice remained but in a wounded form.”

Its impact was immediately felt in classrooms throughout the state. Some teachers and administrators would bristle when students spoke Spanish, Hmong, Mandarin or other languages in the hallways, said Proctor.

“Those attitudes really took hold, and kids quickly learn them too,” said Proctor.

Thousands of bilingual students spent 15 years learning in classrooms that immersed them in English, with little access to other languages. Many emerged from school no longer multilingual or with a weakened grasp of their native tongues, said Genoveffa Grieci, who oversees the school district’s Bilingual Department.

It amounts to the loss of a generation of potential bilingual educators.

According to state data, a minuscule number of the people who took the state’s teacher qualifying test are bilingual. Massachusetts is home to close to half a million Portuguese speakers, according to American Community Survey data. But, from the 2017-18 test results, just 62 among more than 9,500 people (about 0.6%) who took the Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure were native Portuguese speakers.

A little over half of them passed.

While the law was in effect, colleges and universities mostly stopped preparing teachers to lead bilingual classrooms. As the years went on, it became “clearer and clearer that it was an unsustainable law,” said Proctor.

“Principals (of dual-language programs) were constantly talking about how they’d hire teachers because they were bilingual but they would come to the school and they didn’t know what dual language was,” said Proctor. “They were spending all their professional development money at the school to do the basic training of teachers to familiarize them with what they had just gotten themselves into.”

Boston College and other colleges and universities have tried to solve the problem by creating a certificate program to better prepare teachers for dual-language schools.

The English-only law was repealed in 2017.

More than 10 years ago, Framingham even turned its hiring eye overseas through an arrangement with the Spanish embassy. Currently, there are about 25 international teachers who left their homes across the ocean to teach in the district for one- to three-year periods.

Most are from Spain, though one is from Brazil.

In general, the teaching workforce has struggled with a diversity problem. Throiughout the state, as the student population has become more racially diverse, the majority of their teachers are white.

That problem extends to bilingual teachers, said Lesley University education professor Meg Burns.

“One of those forms of diversity is language,” said Burns.

Frozen in time

Now that bilingual education is legal again, Proctor encourages colleges to use modern-day research on bilingualism to shape the way teachers are trained and ultimately create more dynamic programs for children today.

“We basically got frozen in time. In 2002, the research that held sway was from the ‘90s … my concern is now that bilingual education is legal again, we revert to what we knew about the state of bilingual education, rather than take stock of the knowledge that’s been generated in the 21st century,” said Proctor.

Grieci said the district knows it has to “work twice as hard” to make sure it has the right resources and staffing for these programs.

“There’s still a lot of work, we’ve just begun this work,” said Grieci.