creeps in A Florida Times-Union special report

Century of dredging brought wealth, watery risks

By Nate Monroe & Christopher Hong

Beneath a half moon one September night in 1565, just a few days before an infamous hurricane would strike Northeast Florida, the doomed French Huguenot Jean Ribault almost suffered a catastrophic early defeat.

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Ribault’s Spanish rival, discovered a lonely cluster of French ships anchored off the mouth of the St. Johns River. Ribault’s ships were too heavy to navigate the shallow river mouth, which could drop to as little as 6 feet in low tide.

Under cannon fire, Ribault’s vulnerable offshore ships cut anchor and escaped Menéndez’s surprise assault that night, though the near-disaster presaged Ribault’s death and Spanish conquest weeks later.

Sprawling, shallow and unpredictable, the mouth of the St. Johns River menaced navigators for centuries.

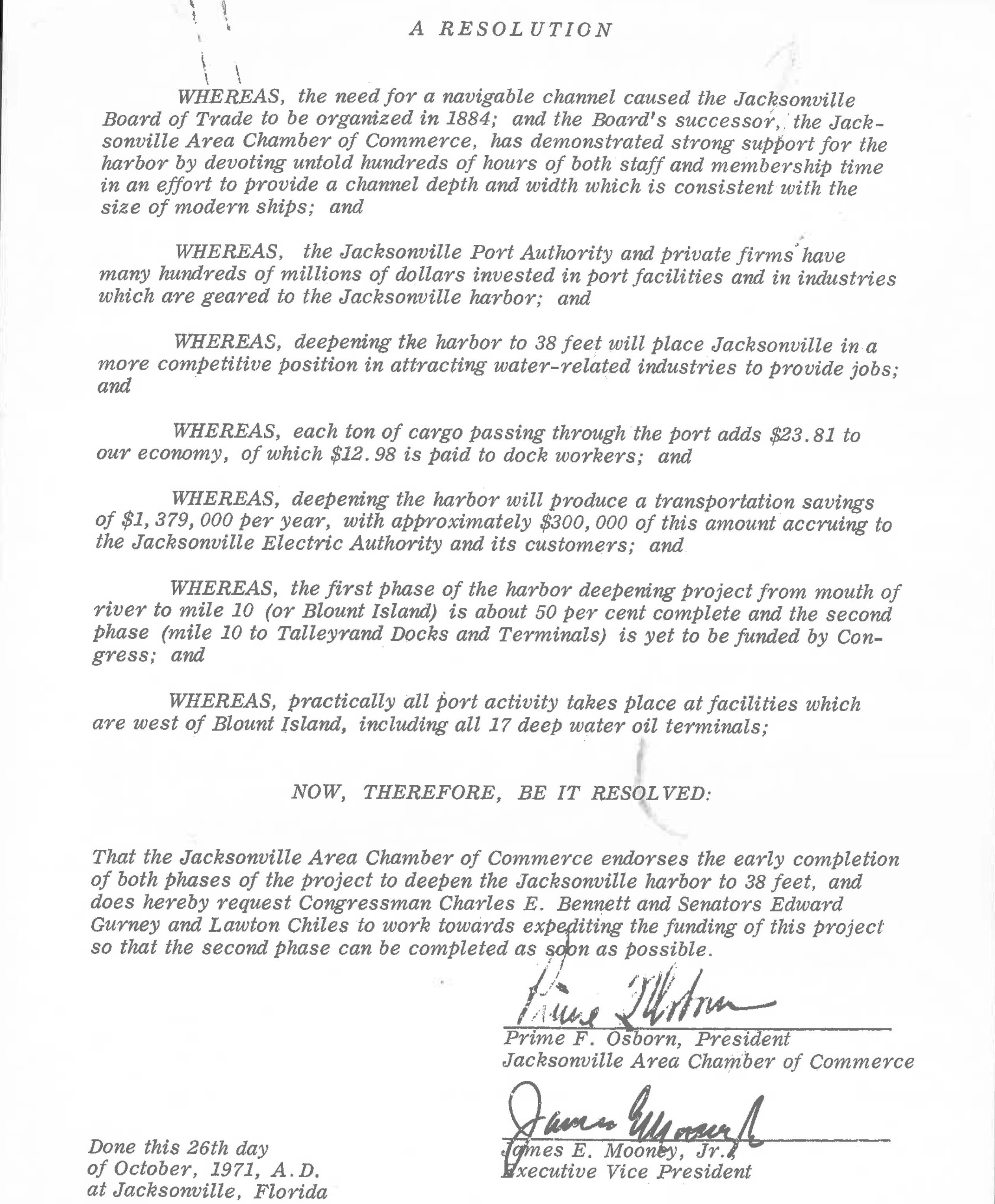

By 1877, a report estimated the uncooperative entrance to the St. Johns cost the region at least $100,000 per year in lost commerce because “vessels leaving port are frequently detained for days, and even weeks, at the bar, waiting for favorable tides and deeper water …”

The forces of industry, however, would not be held at bay forever. Nineteenth-century burghers who came to Jacksonville, a town of only a few thousand residents, had a vision more ambitious than the old empires that fought over the riches of the New World, though it would come with consequences none could foresee at the time.

For more than a century, egged on by generations of city leaders nursing dreams of a deepwater inland port in Jacksonville, the federal government has spent tens of millions of dollars dredging and reshaping the St. Johns River — bending the waterway into a blunt instrument of economic progress and shortening the distance between downtown and the sea along the way.

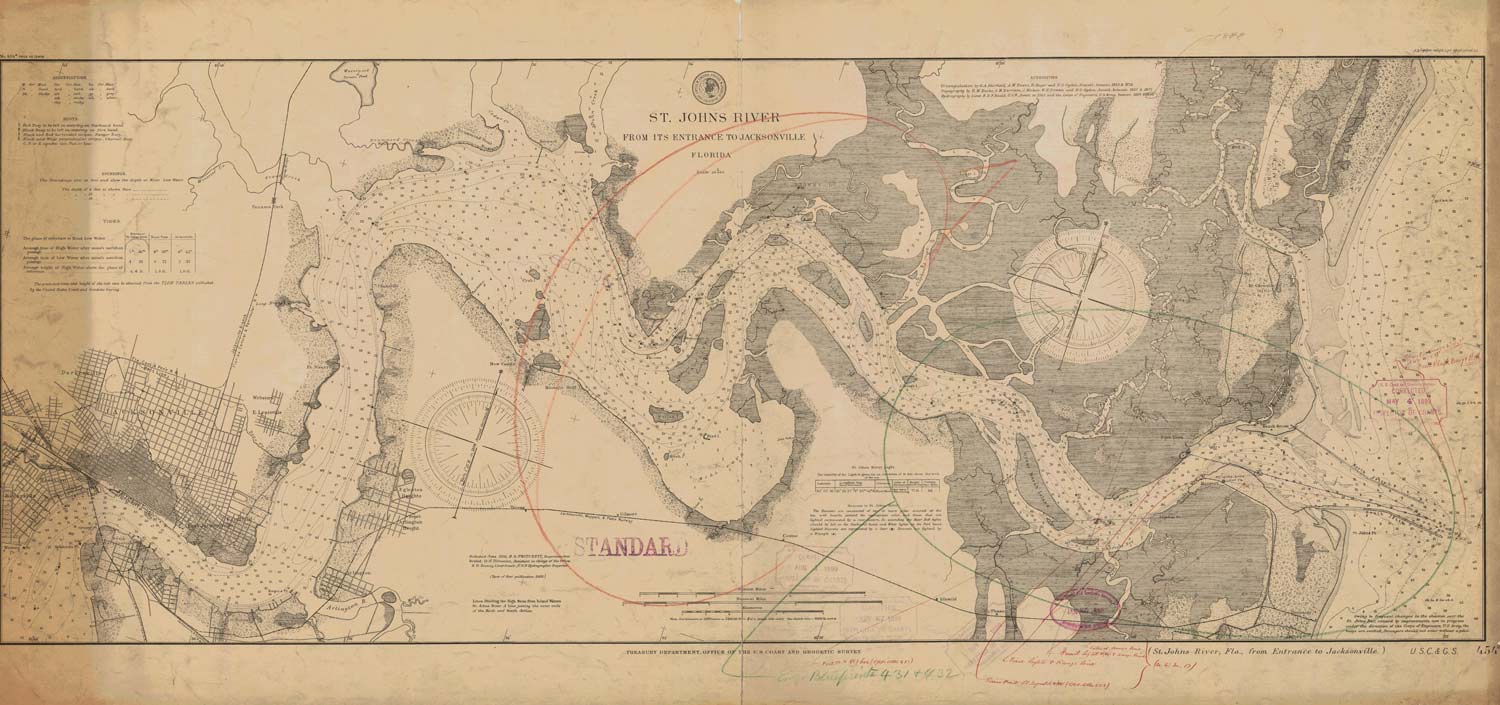

As the modern foundations of the city took root in low-lying floodplains along the St. Johns River, engineers spent much of the late 19th and 20th centuries turning the sinuous river into a superhighway that could carry ever-larger cargo ships to the Jacksonville Port Authority’s inland terminals.

The changes have unquestionably brought economic prosperity and growth to the region, but they also created another phenomenon that looms increasingly large over the city’s future. The river is now a superhighway for Atlantic Ocean water, which in the event of a major storm could present greater risk to downtown and the neighborhoods around it even though they are miles away from the river's mouth.

The Times-Union spent months after Hurricane Irma seeking to understand why the September 2017 storm — a Category 1 storm by the time it reached North Florida — caused a shocking 150-year flood that sent salty seawater gushing into the streets of downtown and an eclectic mix of neighborhoods along the river and its tributaries, and deep into Clay County neighborhoods along Black Creek.

A major reason was simply bad luck: Irma’s approach coincided with higher-than-normal tides typical in that September time frame, as well as an unusually strong and gusty nor’easter that trapped water in the St. Johns River, and inundated the region with rain before Irma’s arrival.

But a review of historical documents and data, U.S. Army Corps reports, court records, City Hall documents and interviews with researchers and legal experts, leads to another unmistakable conclusion: The portion of the St. Johns River that runs through downtown is no longer the lazy waterway of the city’s distant past.

In chasing its dreams of a deepwater port, the city has brought the Atlantic Ocean to its doorstep.

And it did so blind to the risk.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, one of the nation’s oldest federal agencies and the overseer of these changes to the St. Johns River, has never studied how more than a century of work might make the city more vulnerable to storm surge and flooding.

As the federal government deepens the river from 40 to 47 feet — a project that began earlier this year — no one knows the answer to that question. Indications are that it’s an increasingly important one.

Consider:

-Downtown is now divided by a river that more resembles the Atlantic Ocean than at any other time in its past: The currents are faster, the water is saltier and tide movements come earlier and are more extreme.

A pair of researchers who study the effects of river dredging on storm surge and tides say they see preliminary signs that storm surge might have gradually intensified in the St. Johns, as it has in other waterways where the federal government completed multiple dredging projects.

- The Army Corps acknowledges in its own analysis that the latest 7-foot dredging project could increase water levels in a 100-year storm surge by 3 to 6 inches in the main stem of the river, and by 8 inches in areas closer to the ocean.

But the agency — which has nearly unchecked latitude in making such determinations — has, for reasons that are unclear, deemed those potential increases insignificant.

Critics say brushing off those changes flies in the face of a reality that any resident or business owner in a flood-prone area instinctively knows:

“This is a game of inches,” said Kevin Bodge, the senior engineer and vice president of Olsen Associates, a Jacksonville-based coastal engineering firm. “Hurricane Irma very specifically spoke to the importance of just a couple of inches.”

The Army Corps would not comment to the Times-Union on its storm surge analysis or respond to questions because they overlap with issues central to a federal lawsuit against the agency over the 7-foot dredging project.

- Although JaxPort boosters and local politicians have wielded the Army Corps’ credibility as a bludgeon against environmental activists and dredging critics, the agency has a spotty record when it comes to foreseeing or predicting the consequences of its work.

Locally, Mill Cove — a once celebrated fishery wrecked in the years after the federal government rerouted the St. Johns River in the 1950s — is a cautionary tale of sorts about the Army Corps’ ability to foresee the consequences of its actions and its limited ability to fix them.

JaxPort deferred on questions about storm surge to the Army Corps.

- Meanwhile, higher sea levels push water up along the banks at about an inch per decade, a rate that scientists — and the Army Corps — expect could increase in the future.

The Army Corps acknowledged the need to design future projects with sea-level rise in consideration. There’s little apparent sign the 7-foot deepening project currently underway was adapted to deal with that future, even as its own report found “potential impacts of rising sea level include overtopping of waterside structures, increased shoreline erosion, and flooding of low lying areas.”

- City leaders are only just beginning to grapple with the reality that the St. Johns River is rising.

Hurricane Irma caused a historic flood in Jacksonville, ruining homes, businesses and lives — a powerful indication that business as usual won’t cut it for cities that are the most vulnerable to rising seas.

"I think that's what drove the broader conversation locally,” said City Councilwoman Lori Boyer, whose district includes low-lying riverfront neighborhoods that are prone to tidal threats.

But there’s little indication sea-level rise has captured attention in Jacksonville the way it has in other at-risk cities.

Mayor Lenny Curry, a major booster of the dredging project, has shown little interest in talking about the topic.

"It would be nice if they had a plan. I don’t see a plan anywhere yet,” said Bobby Back, a homeowner in a low-lying Southbank neighborhood that flooded during Hurricane Irma and is now part of a voluntary buyout program. The neighborhood has long suffered from so-called nuisance flooding — inundation during high tides — that residents say has gotten worse in recent years.

City leaders hope to one day restore the neighborhood back to a natural floodplain, but Back and his wife, like some of their neighbors, remain attached to their property, which has been in their family for decades.

“We’ve just not seen anything from public works or anybody else to address that,” Back said. “Maybe they can't. I don't know. We have a lot more questions than we have answers."

A new beginning

The St. Johns, which flows 300 miles south to north, is Florida’s longest river, and it’s remarkably flat. The total elevation drop from the headwaters in Indian River County to the Atlantic Ocean is less than 30 feet, or a slope of about one inch per mile.

For much of its expanse, the St. Johns is lethargic, resembling more a collection of shallow lakes than a river in any conventional sense. That begins to change closer to the ocean.

The final 26-mile stretch, beginning near downtown Jacksonville, is influenced by ocean tides and has been heavily engineered, giving it greater average depth — about 30 feet. The Jacksonville Port Authority terminals begin at about mile 11, a stretch where the bulk of future dredging is expected to take place.

The river also narrows in downtown — a mere 1,200 feet wide in one spot — which restricts water flow, a feature the Army Corps notes “is particularly evident during more extreme events such as storm surge …” It was certainly evident in the hours after Hurricane Irma passed through North Florida, when viewers around the nation saw images of floodwater creeping higher hour by hour in downtown as the tide got higher — it crested at about 5.5 feet.

A great fire in 1901 destroyed downtown Jacksonville, and in the prolonged recovery that followed, the city on the banks of the St. Johns River underwent an aesthetic renaissance led by an ambitious New York architect named Henry John Klutho, whose buildings remain important sites today.

It was just years before this era of civic rebirth that Army engineers figured out a way to channelize and dredge the shallow river mouth, paving the way for more than a century of projects to deepen the shipping channel — which once ranged between 10 feet to 18 feet in the main channel — by more than 120 percent, turning Jacksonville’s port into a major economic driver for the region and hastening significant but unwelcome changes of a different sort.

Let's talk about storm surge

There are at least two broad reasons dredging can intensify storm surge for areas that are even miles away from the ocean.

Imagine riding a bike through the forest on a bumpy, winding trail that is obscured by bushes and tree limbs.

Now, imagine riding a bike on a straight and smooth asphalt road. Easier, right?

When a river is dredged to a uniform depth, the natural features that can suck energy out of an incoming wave — underwater sand dunes, rocks, grass beds — are eliminated. That makes it a little more like the smooth asphalt road.

Straightening a river — which the Army Corps did to the St. Johns in the 1950s — can have a similar effect.

“Hence, it's reasonable to think that 'streamlining' would reduce friction and allow more water to move towards Jacksonville,” said Stefan Talke, a Portland State University professor who researches storm surge increases in rivers that have experienced decades of dredging.

The depth of a river also plays a role.

In a shallow river, the top and bottom layers of water are close together, and interact a lot with one another. That’s why it’s common to see turbulence or boiling on the surface of a shallow river — that’s energy being expended.

In a deep river, those two layers are farther apart and interact less, and that means a wave moving up river faces less resistance.

“This is why ‘still water runs deep,’” Talke said.

Greater depth can also explain why saltwater moves farther inland. In a deep river, heavier saltwater on the bottom mixes less with the fresh top layer, meaning there is less resistance to bottom-layer saltwater as it moves inland.

Storm surge modeling can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and is highly technical work — particularly true when trying to measure the effect of more than a century of dredging and engineering projects on a river. It takes even more research to then determine if a change in storm surge intensity would affect an area’s vulnerability to flooding.

It is possible to get some clues about what could be happening with potential changes in the St. Johns River by considering a simple question: Are there any signs that ocean water is gradually having an easier time moving into the river?

It turns out there are.

The St. Johns River did not want to be tamed.

Recent Army Corps documents say dredging began in 1899, but more than 20 years before that, in 1873, the federal government tried an experimental dredge to little effect. The shifting sands made it impossible — it was “like a game of hide and seek,” a War Department report later said.

With an initial appropriation of $125,000 from Congress in 1880, engineers started work on a north and south jetty — rock walls that would extend about a mile out into the ocean and seal off the cross-currents that made the previous dredge impossible. The walls would turn the wide and sprawling river mouth into a channel more suitable for ship traffic, an idea formulated by Capt. James B. Eads, a legendary engineer who used a similar design at the mouth of the Mississippi River that helped revive New Orleans’ port.

It was one of the Jacksonville’s first major public-works projects and would take 40 years to fully build out — an effort plagued by one epidemic, severe weather events and a host of engineering setbacks.

Even partially built, the walls were enormously effective.

The channel, now a more efficient vehicle for ocean water, deepened itself to about 15 feet, and even deeper dredges were right behind.

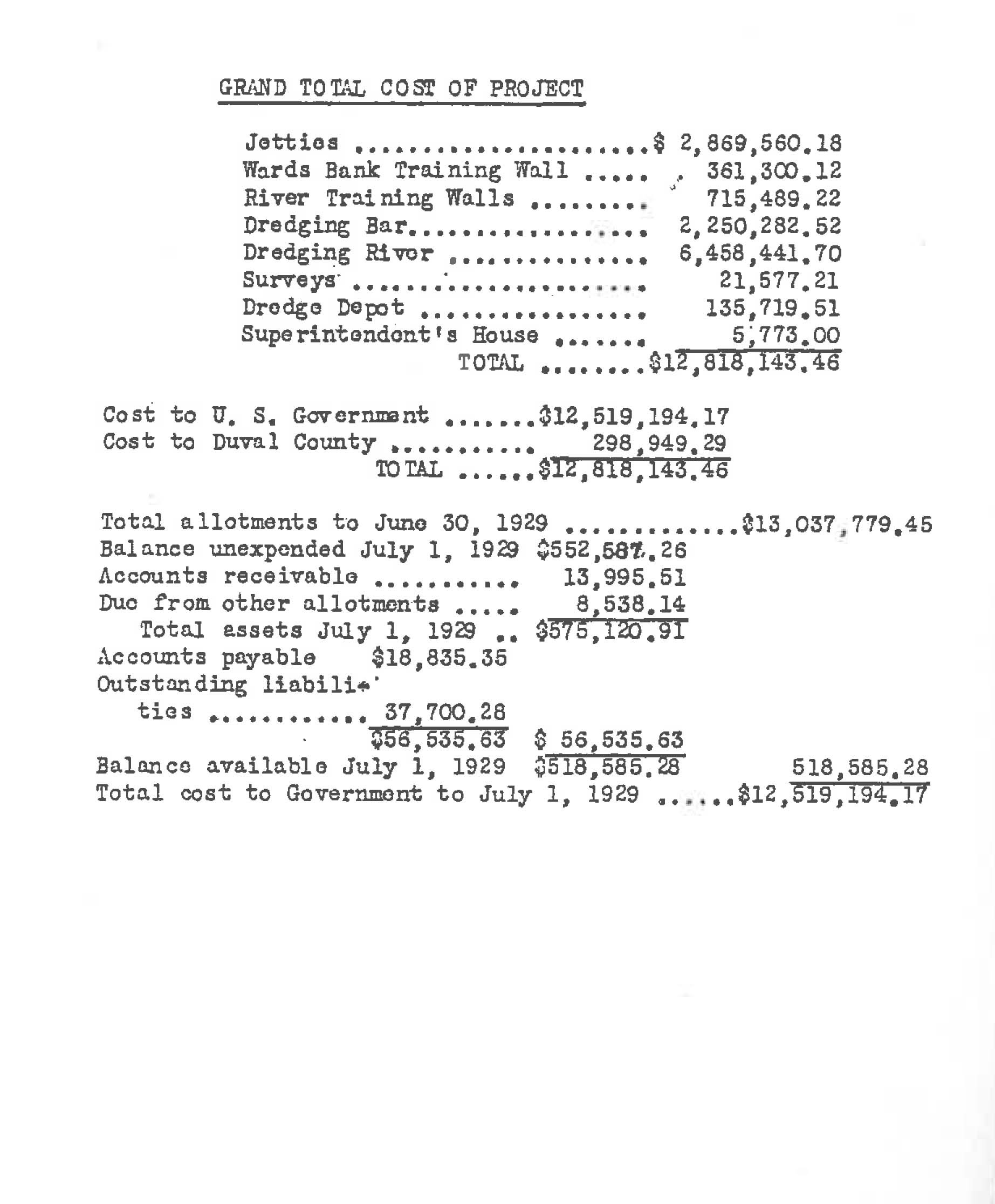

In 1902, the channel, about 18 feet in the main stem of the river, was deepened to 24 feet, and a 30-foot dredge quickly followed. By 1929, the U.S. government had spent about $12.5 million (about $180 million in today’s dollars) on engineering work.

Dramatic changes began immediately.

Engineers who helped build the jetties noticed that the new channel at the mouth of the river invited faster currents. One observed that the banks along St. Johns Bluff — the site of a Civil War battle and one of the highest points in Jacksonville — began “washing away at a dangerous rate.” The same thing was happening as far downriver as Dames Point, about 9 miles from the ocean.

“Banks began to cave in, and hundreds of thousands of yards of sand fell into the channel, which had to be dredged out later at great expense,” according to a 1952 report by a former Army Corps engineering chief.

The government was far from finished.

In 1952, engineers straightened the river by creating a man-made channel, forming what is today Blount Island. This channel allowed ships to bypass a once-meandering series of turns and instead take a straight and narrow east-west passage toward the port terminals.

The cut-off channel reduced the distance to downtown Jacksonville from the ocean by about 1.9 miles. It also sealed off Mill Cove — at one time a locally renowned fishery with deep water — from the natural flow of the river, which became a controversy and fomented hard feelings toward the Army Corps years later.

Arlington homes that once abutted the bountiful cove found the area, now devoid of water movement, transformed over time into a stagnant, muddy marsh.

Today — after multiple rounds of dredging through 2010 — the river depth varies between 40 and 51 feet through the Jacksonville Port Authority’s Talleyrand terminal north of downtown.

Much like the first generation of engineers who manipulated the river, modern researchers notice striking changes taking place within the St. Johns, sometimes happening within single lifetimes.

The saltwater transition zone — where Atlantic Ocean saltwater and river freshwater begin to mix — has moved further upstream through the decades. That zone is thought to have been near the Acosta Bridge in downtown in the 1950s.

Scientists who study the river now see in aerial surveys that the zone has moved dramatically south (grass beds are visible from the air: more vegetation means more freshwater; less vegetation means more saltwater).

Today the salinity zone shifts between the Buckman Bridge near Orange Park and the Shands Bridge near Green Cove Springs, depending on rainfall levels, meaning it has moved between about 10 and 25 miles south of downtown — about 50 miles from the ocean — over the past six decades.

“I remember that I used to regularly see grass beds around Sadler Point north of NAS JAX on regular… surveys during 1994-2000,” said Gerard Pinto, a Jacksonville University scientist who helps compile annual checkups on the state of the St. Johns.

“Those areas are now typically bare of vegetation.”

Scientists are certain dredging is one of among several man-made reasons behind salinity intrusion in the St. Johns River.

A study by the National Oceanographic Atmospheric Administration found that the tide predictions it had used since 1934 were off by as much as an hour at the mouth of the river when measured again in 1998. One cause of the earlier tides: dredging.

“In the past sixty years, the currents (and to a lesser extent, the water levels) in the St. Johns River have been significantly affected by extensive dredging of channels and harbors, new channel construction, and other natural and man-made modifications that have occurred over the years,” the study said.

Tides and storm surge

Talke, the Portland State researcher, and his colleague, Ramin Familkhalili, are some of the few engineers in the nation studying the cumulative effect that years of deepening projects can have on tides and storm surge intensity within estuaries.

In basic terms, their hypothesis goes like this: Storm surge and tides — both of which are known as “long waves” or “shallow-water waves” — share similarities in how they move through water.

So if the tidal range — the difference between high tide and low tide — has increased over many decades, that might indicate the storm surge intensity has increased as well. (A larger tidal range — say, an increase of 1 foot over 50 years — means that high tide would be a half-foot higher, and low tide a half-foot lower.)

Talke and Familkhalili found such a change in the Cape Fear River in Wilmington, N.C., a waterway that, like the St. Johns, has undergone a number of dredging projects in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The results of the study, the two wrote, “suggest a simple but profound lesson: locations in which tide waves have been amplified are also vulnerable to increases in storm surge and flood risk …”

The increased tidal changes Talke and Familkhalili tracked are less pronounced along coastal areas and more pronounced further inland, suggesting, they argue, that the cause of those changes lies within man-made alterations to the river rather than driven by large-scale ocean changes like sea-level rise, itself the result of human activity warming the climate.

That also means any increase in storm surge intensity would be felt in those more inland areas, too.

Part of the trick is gathering enough historic tidal data to be able to measure whether or how the tide is changing in a river.

Talke and his colleagues have uncovered archival tide records the federal government was unaware it still had, and that in some cases have doubled the length of the records that are publicly available at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Climate Preparedness and Resilience Office — which is part of the Army Corps — has shown strong interest in Talke’s work uncovering those records.

Talke hasn’t found the same kind of extensive historical tidal records in the St. Johns that helped with the Cape Fear study, but a preliminary look at what is available in the St. Johns show at least one remarkable similarity to Cape Fear.

An 1879 annual report from the chief of engineers makes reference to the tide range in downtown Jacksonville measuring about one foot. Today, the range is about 1.8 feet — nearly double. Like Cape Fear, the increased tide range near the coast is much smaller than that, suggesting that man-made activities like dredging are the source of the change.

“It has definitely increased,” Talke said of the tide. “The obvious question is if that’s something important or not in terms of flood increase.”

Notably, the Army Corps’ own report on the 7-foot project didn’t just project potential increases in storm surge. It also found that the dredge could raise the height of high tide by about 1.8 inches in parts of the river.

What a worst-case scenario would look like in downtown Jacksonville still isn’t clear: Hurricane Irma’s peak storm surge hit at low tide. It wasn’t until later in the morning on Sept. 11, as the tide climbed higher, that devastating flood water surged into downtown and other neighborhoods.

The changes observed in the St. Johns for years show that downtown Jacksonville is more connected to the Atlantic Ocean than ever.

There is little doubt dredging is one of the major reasons for this.

“Knowing the causes and consequences of past development gives us knowledge and the potential to make more informed decisions about infrastructure investment,” Talke said.

“Understanding the past, in other words, can help us design for the future.”

We haven't really talked about storm surge before, and that's a problem

Before Hurricane Irma, there was virtually no focus on the impact to storm surge intensity throughout the years-long debate over the Army Corp’s 47-foot dredging project — even after the agency released its collection of studies, called an “environmental impact statement,” in April 2014.

Most of the concern centered around potential ecological damage, like saltwater intrusion and harm to sea life like manatees.

A task force stacked with members of Jacksonville’s business community, convened under former Mayor Alvin Brown, found in 2015 that the Army Corps’ plan fell far short on mitigating for those possible changes and recommended spending about $50 million more for environmental work.

Brown’s successor, Mayor Lenny Curry, disbanded the group before it had finished issuing its findings.

Environmental activists are now sounding the alarm about storm surge, but the Army Corps is unmoved.

The St. Johns Riverkeeper — a well-known local environmental watchdog — late last year amended an existing federal lawsuit seeking to stop the 7-foot dredge to include an argument that the Army Corps failed to properly study storm surge intensity and its flooding impact.

U.S. District Judge Marcia Morales Howard in January denied the Riverkeeper’s request for an emergency halt to the project, but she left the door open to allow the Riverkeeper to argue its case down the road.

A major point of disagreement between the Riverkeeper and the corps is whether the agency’s storm surge study — which acknowledges that the 7-foot dredge could increase storm surge height by as much as 8 or 9 inches in parts of the river close to the dredging project — downplays the potential risks.

The Army Corps’ concluded that the potential increases in storm surge are insignificant.

It’s not clear in the report, however, why the Army Corps came to that conclusion.

"That's what I think is missing from this document,” said Jessica Wentz, a staff attorney and researcher at Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

Wentz said the storm surge report appeared to be a bit more detailed than in some of the past Army Corps studies she has reviewed, but it’s hard to understand why the agency would “dismiss (potential storm surge increases) as inconsequential without really explaining why.”

“They don't really emphasize the fact that we're already going to see problems ... even if this project only exacerbates those problems a little bit,” she said.

It’s not clear what it would take for the Army Corps to determine that an increase warrants more attention.

In Charleston Harbor, S.C., for example, smaller projected increases in storm surge from a planned dredging project seemed to be of more concern to the Army Corps.

Jacksonville and Charleston were part of an Obama-era initiative called “We Can’t Wait” that fast-tracked harbor deepening studies along the East Coast by 14 months. Charleston’s project, which began in March, seeks to deepen the harbor from 45 to 52 feet.

A 2016 storm surge study for the Charleston project found potential storm surge water level increases in the harbor ranging between about 1.2 inches to a maximum of about 3.6 inches — the lower end of what the Army Corps expects could happen in Jacksonville.

That was enough for the Army Corps to “proceed with a more refined and more accurate analysis to quantify the potential project impacts” that “includes the floodplain areas surrounding the Charleston Harbor estuary.” Those findings were spelled out in a “Phase II” storm surge analysis.

In Jacksonville, the Army Corps dismissed the potential increases in water levels without indicating the need for a more refined study.

After Irma, the agency doubled down on its position. It said the flooding issues “do not constitute significant new circumstances or information relevant to environmental concerns bearing on the project or its impacts.”

In denying the Riverkeeper’s request for an injunction in January, Morales said the lack of public focus on storm surge through several years of public hearings and debate over the dredging project might ultimately hurt the Riverkeeper’s case.

Dredging the St. Johns River

1880

1880: Work begins on jetties at river mouth

1894

Completed 15-foot deep navigational channel from Dames Point (mile 11) to Mile Point (mile 5)

1896-1906

24-foot dredge from Jacksonville to the ocean and extending jetties - completed 1906.

1916

30-foot dredge completed from Jacksonville to the ocean

1930

Widen bend at Dames Point to 900 feet.

1945

The river channel deepened to 34 feet and the Dames Point Fulton Cut made — Federal Project 26.8 miles long.

1978

38-foot dredge completed.

1998-2004

Mile 15 to mouth of the river deepened to 40 feet.

2010

Drummond Point to Talleyrand (5.3 mi)from 38 to 40 feet.

“It’s unclear whether anyone criticized the Corp’s storm surge modeling or the lack of a more elaborate flooding analysis before the eve of dredging … (which) could cast doubt on the significance of those concerns,” she wrote.

The Army Corps, the Riverkeeper and Morales do seem to agree on at least one point: the storm surge study is not a flooding analysis. The rub is whether the Army Corps should be required to complete one.

The question seems simple enough: If Irma flooded thousands of homes and businesses with a 40-foot shipping channel, how many more would flood when it’s deepened to 47 feet?

The agency argued that it modeled the potential difference in storm surge and tides but that flooding depends on a number of variables, many of which are not related to dredging. The Army Corps also said it’s under no obligation to model for “every conceivable storm event." That was an answer to the Riverkeeper’s criticism that the storm surge analysis ignored nuisance flooding — flooding at high tide — that has plagued neighborhoods like San Marco for years.

The agency did, however, tell the Riverkeeper in correspondence that, “based upon engineering judgment,” it estimated that the 47-foot dredge could increase water levels during less severe, more regularly occurring storms by 12 percent or less.

The corps also didn’t include rainfall in its modeling, which the agency says is appropriate but that the Riverkeeper finds perplexing since extreme storm surge will almost always coincide with rain.

There is actually an emerging body of research on what are called “compound events” — storms that bring with them both flood-level rainfall and storm surge — that suggest such storms are becoming more common, and that the federal government’s method of calculating a community’s flood vulnerability might underestimate the real risk.

Such risks are particularly pronounced for cities divided by urban waterways.

“Jacksonville is an obvious example,” said Thomas Wahl, a University of Central Florida professor who is an expert on compound storms.

Regardless, the Riverkeeper faces a difficult path challenging the Army Corps’ findings.

It's hard to beat the Army Corps in court

President Richard Nixon in 1970 signed the National Environmental Policy Act, a watershed law that requires federal agencies to prepare detailed statements outlining the potential environmental impacts of all major actions, like Army Corps navigation projects. It was the federal government’s response to an increasingly environmentally conscious public, and it ushered in public participation and the elevation of environmental concerns when the government planned projects.

By that point, however, the St. Johns River had already been significantly re-engineered: the Army Corps had created the streamlined channel at Blount Island nearly 20 years before and had already dredged the shipping channel to 38 feet. In the years since, the deepening projects have been comparatively small.

Any damage, in other words, had already been done, and the new baseline by the late 20th century was a remarkably different river than the one Jacksonville’s founding fathers brought to heel.

Whether the Army Corps complied with its obligations under the National Environmental Policy Act, however, is at the heart of the Riverkeeper’s lawsuit seeking to stop the 47-foot dredging project.

There are limitations to what NEPA truly requires agencies to do. It’s a procedural law that on its own simply means the government has to take a “hard look” at environmental issues stemming from major actions it plans to take in an organized and public way.

“It does not dictate what the decision must be,” according to a 2008 report from the Congressional Research Service. “More specifically, it does not require the agency to select the least environmentally harmful alternative or to elevate environmental concerns above others.”

The Army Corps, for example, must solicit public input as well as feedback from other federal agencies on projects it plans, and it must respond to them. But — aside from compliance with specific laws like the Clean Water Act — the corps is not required to incorporate that feedback into its planning.

In some cases, responding to feedback on the 47-foot project, it didn’t.

Another key point about the NEPA process: It’s forward looking, meaning the Army Corps has to give some nod to the cumulative effects of past work, but not nearly to the degree that it analyzes the incremental change the project at hand might cause. There is no requirement that the Army Corps study how more than a century of dredging has intensified storm surge heights in the St. Johns River.

"Generally you see an effort to narrow the range of things you have to consider when you make a decision,” said Mark Davis, the director of Tulane University’s Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy and the ByWater Institute.

“I think the rulebook that agencies have often worked with in the past are not the rulebooks we should be using in the future,” he said. "The modeling toolbox was not setup for a world where you have the potential for far bigger storms and where sea levels are projected to be rising."

Wentz, the Columbia researcher, said while the Army Corps generally acknowledges sea-level rise when studying a potential navigation project, the “analysis of storm surge and flood risk is often lacking.”

But challenging an agency’s compliance with NEPA is daunting. In general, it’s always difficult to defeat a federal agency in court — a legal doctrine called sovereign immunity — and the Army Corps enjoys additional legal protections beyond that.

In sum, courts must give the Army Corps the benefit of the doubt, and that means in a battle of experts, the Army Corps will almost always win.

The Army Corps, Morales noted in her court order, “must have discretion to rely on the reasonable opinions of its own qualified experts, even if … a court might find contrary views more persuasive.”

'Action talks. Other stuff walks.'

Like the Army Corps, city officials don’t appear inclined to second guess their enthusiasm for St. Johns River dredging.

Dredging has long been championed by Jacksonville business leaders, a historically influential group that bankrolls candidates for city offices. In addition, the Jacksonville Port Authority for years touted an increase in jobs the deeper channel would bring — through the credibility of those rosy projections also have been debated for years.

“The days of endless conversation and study groups are behind us. We are on the move,” Mayor Lenny Curry tweeted the day the corps began the dredging project. “Action talks. Other stuff walks.”

The rising St. Johns River presents a challenge to City Hall that doesn’t fall along the familiar “Tale of Two Cities” dichotomy that has played out in Jacksonville for decades on issues like wealth, education and crime.

Irma’s floodwaters inundated many poor neighborhoods along feeder creeks to the St. Johns: Hogan, McCoys and Moncrief creeks, and the Trout and Ribault Rivers. It also swamped some of Jacksonville’s wealthiest neighborhoods that front the main stem of the river like Ortega.

The flood caught nearly everyone off guard.

Rescue crews plucked panicked residents out of their homes in San Marco and Riverside (a neighborhood where, in perhaps an ironic twist of fate, some of the roads are named after Army engineers who oversaw the construction of the jetties at the mouth of the St. Johns: Lomax, Gilmore, Rosselle).

One of the most shocking images in the hours after the storm passed was flood water cascading into the basement of the Wells Fargo tower in downtown as the tide climbed higher. The building, one of the city’s most iconic, was closed for weeks.

“...our office was shut down for an extended period of time and forced to relocate to a temporary location for approximately two months,” Jacksonville attorney Seth Pajcic wrote to Morales, the federal judge overseeing the Riverkeeper’s lawsuit against the Corps.

“It is likely the that the high salinity levels in the St. Johns River made the efforts to restore the computer and electrical systems in the building much more difficult.”

The city sends mixed signals about how urgently it views sea-level rise and resiliency issues. It’s not clear what Curry’s views are on climate change, and his office did not respond to a request for an interview.

Curry, for example, praised President Donald Trump on the day he announced he was pulling the United States out of the Paris Climate Accord, a global agreement to curb greenhouse gases that are warming the climate.

The city also pulled out of the “100 Resilient Cities” program awarded under Curry’s predecessor. Even though that program carried relatively little financial assistance to combat disasters and sea-level rise, critics said Curry’s decision betrayed a lack of interest in the topic all together.

“Mayor Curry has consistently supported policies to expand economic opportunity and create jobs. For that reason, he is supportive of preparing JaxPort to take advantage of changes in the shipping sector,” said Brian Hughes, Curry’s chief of staff in a statement.

“As for storm resiliency, Mayor Curry is working every day as part of his public safety agenda to prepare for threats, including potential weather events. The administration continues making substantial investments in infrastructure across our city, and part of that investment is dedicated to drainage and hydrology.”

Last year, the city began working on a state-mandated change to its 2030 master plan that acknowledges in writing the need to prepare for sea-level rise and establishes a working group to start studying the issue within the year.

That change faced skepticism from the city Planning Commission — which recommended the City Council not pass it based on fears it would be onerous to business owners.

Some council members seemed initially reluctant to support the master plan change because of the inclusion of the term “sea-level rise.”

“A lot of the time when we have a flooding issue, it's not due to a sea level rise ... it's due to a blocked drain ...” City Councilman Al Ferraro said during a meeting over the legislation.

In the aftermath of the hurricane, some attention focused on Jacksonville’s stormwater drainage system, which has had long and well-documented inadequacies especially in the city’s poor neighborhoods. But Hurricane Irma actually exposed a more fundamental and vexing problem: What can the city do when the place it sends stormwater overflows?

The St. Johns River is a federal navigation channel that falls under the Army Corps’ jurisdiction. Even modest work the city wants to complete on the river and its tributaries needs the agency’s cooperation, expertise and, often, significant federal funding.

It can take years for these projects to materialize.

Earlier this year, for example, the City Council signed off on an agreement with the Army Corps for a small dredging project that will remove sediment buildup and invasive vegetation in Big Fishweir Creek at the southern edge of the Avondale neighborhood — the kind of project that can in theory improve salinity levels and even storm surge if it were applied on a larger scale to the maze of tributaries along the St. Johns.

That one project, however, took more than 10 years to get to this point and will cost the city $2.5 million — about 35 percent of the $6.5 million total. Construction is expected to start next year.

Practically speaking, City Hall has a limited traditional toolbox.

The city is responsible for efficiently ferrying rainfall into the river, or to use retention ponds and greenspace to absorb stormwater and prevent buildup, a task complicated by a further obligation to manage pollution from that runoff.

For areas closer to the river or its tributaries, the city can try to raise infrastructure like roads and utilities — as long as that doesn’t interfere with the gravity system needed to drain rainfall or simply pushes floodwater onto lower-lying areas. It can also look to planning and zoning rules to try and manage waterfront development.

City Hall also relies on a regional regulatory agency, the St. Johns River Water Management District, to help oversee private stormwater management. That is not an easy task. A resident, for example, who infills their backyard with sand might create a drainage problem for neighbors — but absent a complaint, that is akin to searching for a needle in a haystack.

It’s clear the normal ways of doing business are not enough anymore.

"Jacksonville tends to not to be cutting edge on many things,” said Boyer, the City Councilwoman. "We're not the early adopters of many new things that are going on."

Boyer’s district includes waterfront areas along the Southbank that frequently grapple with flooding.

The city is looking at another option: offering buyouts to residents in flood-prone neighborhoods and converting those areas back to greenspace.

Buyout programs come with their own set of uncertainties. Namely, the efforts require federal money and buy-in from residents who may feel emotional attachment to their homes and neighborhoods, as well as millions of dollars in federal money.

In the Reed Subdivision and South Shores neighborhood — a 1920s–vintage community off Atlantic Boulevard west of Bishop Kenny High School that suffered flood damage during Irma — the city is hoping a flood–mitigation grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency will cover about three–quarters of the cost of buying out up to 72 properties.

That would cost about $10.8 million, with the city chipping in about $2.7 million.

Of that total, only 42 homeowners have expressed interest in the program, according to an April status report on the project.

Back, the Reed Subdivision resident whose home suffered about $100,000 in flood damage during Irma, said he and his wife filled out an application, but it was only to keep their options open.

As he’s watched nuisance flooding problems worsen over the past decade, Back said the city’s lack of answers has been frustrating.

"Maybe a plan means we have to go,” he said. “That very well could be, (but) tell me why. Tell me something other than we can't do anything."

Hard to defeat in the courts, wielding immense discretion over how it designs projects, experts said there is nonetheless one thing the Army Corps does tend to respond to: public pressure.

At minimum, Hurricane Irma was a wake-up call, but it’s not clear the public or government are galvanized to tackle Jacksonville’s flooding problems.

“I think we have to respect nature a little bit more in terms of the power,” Boyer said. “Some of it just can't be crammed in a bottle to the extent we did for so long.”

Shortly after the storm, U.S. Rep. Al Lawson wrote a letter to Mick Mulvaney, Trump’s director of the Office of Management and Budget, requesting $79 million to pay for 11 flood and storm-surge projects in the city. He also wants money to pay for the Army Corps to study flooding problems in Jacksonville.

It’s not clear that money will ever materialize.

"The lesson that is taught by all of this, communities need to be far more engaged and far more informed,” said Davis, the Tulane professor.

“And the moment you start mailing it or treating it as a philosophical issue ... is the moment you start living at unnecessary risk."

About the reporters

Nate Monroe has covered City Hall at the Florida Times-Union since 2013, following reporting stints at the Pensacola News Journal in the Panhandle and the Daily Comet in Thibodaux, La.

Christopher Hong has covered City Hall at the Florida Times-Union since 2013. Previously, he was a reporter at the Citizens' Voice in Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

About this project

Times-Union reporters Nate Monroe and Christopher Hong spent months reviewing historical documents and data, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reports, court records, City Hall documents, and interviewed researchers and legal experts. That work led to one unmistakable conclusion: A century of dredging and engineering has turned the once-lazy St. Johns River into a waterway that more resembles the Atlantic Ocean than at any other time in its past. The river on our doorstep has saltier water, faster currents, and tides that come earlier and are more extreme. In a major storm, dredging may have also led to more intense storm surge for neighborhoods that are even miles upriver. City leaders were blind to those risks.

Web design by Derek Hembd.

Video footage by Michael Jones.

Special thanks to The Jacksonville Historical Society, whose archival records were invaluable; Chuck Meide for his article, "The Lost French Fleet of 1565: Collision of Empires," from which this report used information; Stefan Talke and Ramin Familkhalili at Portland State University, whose research was integral to this story; and many others quoted and not quoted in this story who were generous with their time and expertise.

The cost of the jetties

A portion of a War Department report tabulating the total cost of building the north and south jetties at the mouth of the St. Johns River, which took 40 years to complete. (Jacksonville Historical Society archives)

The cost of the jetties

A portion of a War Department report tabulating the total cost of building the north and south jetties at the mouth of the St. Johns River, which took 40 years to complete. (Jacksonville Historical Society archives)