Left behind

This story was first published on June 26, 2016.

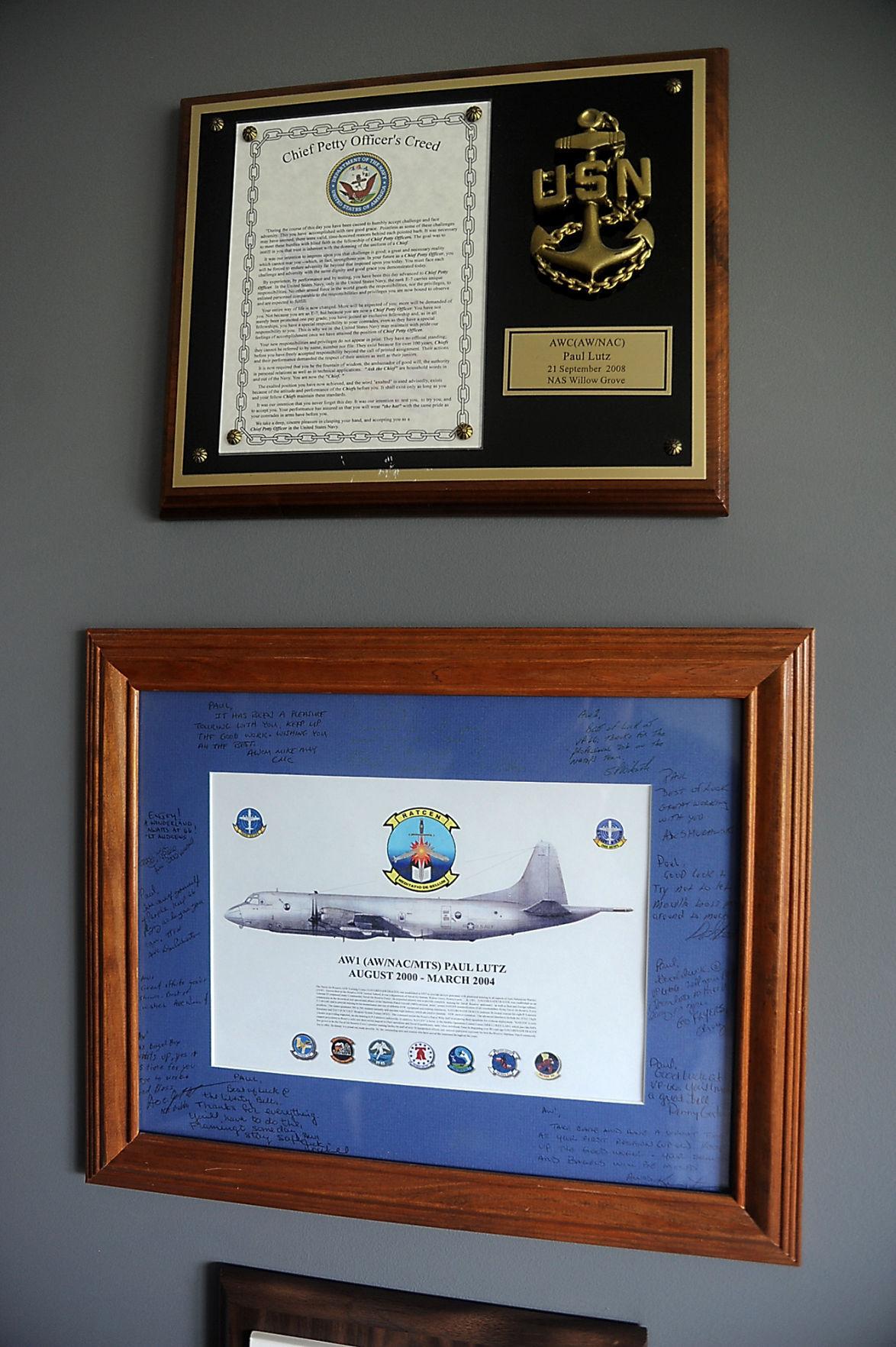

Paul Lutz spent 12 years working on the former Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Willow Grove and says he has been following the headlines about water contaminated with perfluorinated compounds in the area over the past several months.

But there’s one thing missing, the 44-year-old Lehigh County resident says.

“Nobody’s talking about the men and women who served on the base,” Lutz said.

For Lutz and others like him, that’s a problem. He’s one of the most active members of a Facebook group of more than 1,600 people, mainly veterans and their family members, who believe their time at “The Grove” made them sick because of perceived exposures to various chemicals. Naval operations ceased and the base closed in 2011; the Horsham Air Guard Station still operates on a portion of the property.

As to exactly which chemicals they were exposed, they’re not sure. Some point to toxic volatile organic compounds, which were first found in the base’s drinking water in the 1980s. Others wonder if they were somehow exposed to chemicals from known, large fuel spills that occurred on the base over time or more commonly known substances such as arsenic and lead. Still others wonder if their illnesses could have been caused by perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), which although only recently found in drinking water, could have been present as far back as the 1970s.

Or, some say, perhaps it’s a little bit of each.

“Let’s say I was exposed to PFOS. So yeah, it might be bad for you,” Lutz said. “But what happens if I’m taking in that and also benzene (a chemical found in jet fuel)? What about those reactions?”

Looking for details

Lutz believes the military has not been forthcoming with information about potential health risks to personnel.

Leading up to his retirement from the Navy in 2012, Lutz says he began to experience chronic back pain. Once retired, he went to various doctors until one finally ran imaging tests and found he has multiple myeloma, a cancer of plasma cells in bone marrow that can cause bone weakness and fractures.

“I know I’m going to die from myeloma. It’s not like something I’m going to live with and be 95 years old,” Lutz said.

He began radiation treatment last year and chemotherapy treatment in May, but the cancer is considered incurable.

Lutz, a husband and father of three, says his illness has been recognized as being caused by his time in the service; it has been deemed “service connected” by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, meaning he’s eligible for monthly disability compensation.

Lutz says the VA never detailed its reasoning for the designation. But, he says, as a flight engineer worked extensively with petroleum products while refueling airplanes. According to the American Cancer Society, some studies have linked benzene, a chemical found in jet fuel, to multiple myeloma, and a review of VA records by this news organization found that veterans elsewhere have had the illness deemed service-connected because of exposure to fuel.

The VA does not have a policy recognizing a connection between jet fuel and its components and cancers, but it “is aware that this is a common concern among veterans,” a VA spokesperson answered in an email. “VA continuously monitors scientific and medical literature and is interested in potentially designing a study to gain knowledge on this issue.”

The VA can only address similar health diagnoses from a collective group of personnel who were stationed at a common base or deployment in cases where “special exposure scenarios” have been identified, the spokesman explained. The VA has registry programs for veterans in such scenarios, for example, as those who may have been exposed to Agent Orange, or those who were exposed to a variety of potentially harmful substances during the Gulf War.

“VA does not currently have a method to track personnel on service at a particular base otherwise,” the spokesperson added. However, the VA and the U.S. Department of Defense are working to develop an “Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record, which could potentially fill this gap in the future.”

Some members of the NAS JRB Willow Grove Cancer Diagnosis Facebook group, believing they may have been made ill by chemicals on the base, say they have been denied service connection or are skeptical of trying to prove a connection. That’s according to Valerie Secrease, a 64-year-old Franconia resident who worked at the base in Willow Grove for about 26 years as a civilian and reservist.

Secrease is one of the administrators of the Facebook group, which was created in early 2013 by the widow of a veteran who died from cancer that ultimately was deemed service connected. Secrease maintains a private list of former personnel who’ve been diagnosed with or succumbed to cancer and other illnesses, and says it now numbers more than 100, including individuals who have been denied service-connected benefits.

“It seems like every two weeks somebody is dying,” Secrease said, adding that the most commonly referenced cancers are of the throat, stomach, colon and bladder.

Secrease also suffers from health issues; she’s been diagnosed with malignant melanoma and thyroid disease, and also wonders if her high cholesterol and high blood pressure may have been caused by her time at the base. She has not yet applied to have any of the illnesses service connected, and says she isn’t encouraged by the attempts others have made.

“Many of (the people) on the cancer page have been denied compensation because they (the VA) say there is no proof of service-connected disability,” Secrease said.

Secrease and Lutz both say that environmental contamination of various chemicals used at the base was common knowledge among personnel, but it’s only in retrospect that they view it with any alarm. Along with fellow personnel, Secrease and Lutz recall fuel leaks, water fountains closed off with plastic for unknown reasons, high lead level notices, and soil being removed from various sites for disposal. There were never any widespread concerns or warnings, they said.

“When you’re not conscious of it or not sick, you don’t really think about that stuff,” Lutz said. “You know in the back of your mind ... but you don’t think it’s going to be right on top of you. You’re worried about flying airplanes, not about what’s in the water.”

A history of contamination

That hazardous chemicals have been found in the soil, groundwater, and even drinking water at the 1,200-acre former joint reserve base is well-documented.

In 1995, the Willow Grove base and adjacent Air Force property were added by the Environmental Protection Agency to its list of national Superfund toxic waste sites. Numerous areas on the bases were designated as “potential sources of contamination” by the EPA, including sites related to aircraft maintenance, fuel operation, personnel training, stormwater retention and washing areas.

The EPA lists 28 different “contaminants of concern” at the former base, including a number of known carcinogens. Nine of the contaminants have been found in groundwater, the rest in soil, according to the EPA.

Known contamination goes back even further than 1995. Military records reviewed by this news organization show that in 1979, the bases’ drinking water systems were tested for trichloroethylene (TCE), a degreaser used to clean machinery and a known carcinogen. Tests confirmed its presence, along with a similar chemical called tetrachloroethylene (PCE), at levels well above the EPA’s current drinking water standards.

Historically, the Horsham bases had used three wells for drinking water: two on the joint reserve base, and a third on what is now the air guard station.

Documents reviewed by this news organization indicate that the military changed which wells it used for drinking water several times between 1979 and 2014, when all well water was deemed unsafe to drink because of perfluorinated compound contamination.

In early June, this news organization reached out to the Navy’s Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) program and personnel at the air guard station to ascertain which wells were used for drinking water at which times, and when filtration systems were installed to remove TCE and PCE from the water.

The Navy’s BRAC office had not sent an answer as of Friday. Jacqueline Siciliano, environmental manager for the air guard station, said in an email that all wells on air guard property had been abandoned decades ago, and that the base has regularly alternated between the two Navy wells to provide drinking water to its personnel.

Despite the long history of environmental contamination, an extensive review of available documentation found that no analysis ever performed at the base concluded that the presence of the chemicals would have caused a widespread health hazard to personnel.

The most recent and conclusive report is the 2002 Public Health Assessment performed by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, a division of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention responsible for assessing public exposure to toxic substances. It analyzed the possible effects of contaminants known to have been found above EPA drinking standards in the base’s water system.

Even personnel on base before TCE and PCE were cleaned from the drinking water shouldn’t have been affected, according to the agency. The 2002 report acknowledged that six contaminants had been found at levels above the EPA’s drinking water standards but calculated that the amount and length of exposure was not expected to have led to illness.

The report used a “conservative” approach that assumed personnel would have consumed daily the highest amount of each chemical ever found in drinking water on the base. For TCE, that was 300 parts per billion, or 60 times the EPA’s standard of 5 ppb. For PCE, it was 91 ppb, or more than 18 times the EPA’s current standard.

Arsenic, lead, barium and a man-made chemical called 1,1-dichloroethylene also were analyzed after being found above EPA drinking water standards.

The report assumed military personnel would have been on the base a maximum of six years and drink two liters of water a day, and civilian workers for 30 years, consuming one liter of water a day. It also incorporated lower body weight for children who lived on the base.

After running the numbers based on EPA cancer risk models for each contaminate, the agency found that, with the exception of arsenic, none would be expected to cause more than one extra case of cancer in a million people, which is the EPA’s acceptable risk level.

For civilian employees, the agency found that an extra 1.4 cancers per 10,000 people would be expected due to arsenic. However, the report downplayed the findings, suggesting prior studies that established how much arsenic was safe to consume were flawed and didn’t match the situation at the joint reserve base.

“EPA classified arsenic as a carcinogen based on epidemiological studies where people consumed water containing 170 to 800 ppb arsenic for a 45-year exposure period. The maximum detected arsenic concentration in station wells was 22 ppb,” the report stated. “The study (also) failed to account for a number of complicating factors, including exposure to other non-water sources of arsenic, genetic susceptibility to arsenic, and poor nutritional status of the exposed population.”

The analysis also acknowledged that while some individuals may have been exposed to additional amounts of chemicals in soil and different water bodies on the base, that was not factored into its risk calculations.

“In these areas ... contaminant concentrations are below state and federal regulatory limits and below levels expected to result in illness or harm from exposures during recreational activities,” the report stated.

Lead was also found in the drinking water, the report stated. In 1985, it was detected at 20 ppb, higher than the EPA’s present drinking water standard of 15 ppb. Despite analyzing health risks for children who may have lived on the base for up to six years, the agency concluded that the 20 ppb lead level, along with levels of other contaminants, were not “expected to cause adverse health effects in adults or children.”

A spokesperson for the agency did not directly answer a question from this news organization about whether it would still come to that same conclusion today.

The spokesperson wrote in an email that the lead level of 20 ppb and arsenic level of 22 ppb were collected at an on-base supply wellhead, and not an exposure point such as a tap in on-base housing or work places.

“Given the distribution and potential mixing, it is difficult to estimate what the on-base personnel (including personnel and their families who resided on base for periods of time) were exposed to at the tap in the past,” the response stated.

In addition, the response noted, the Navy implemented measures to prevent exposures as soon as contaminants were detected in the supply wells.

The human risk

Despite the long history of environmental contamination, an extensive review of available documentation found that no analysis ever performed at the base concluded that the presence of the chemicals would have caused a widespread health hazard to personnel.

The most recent and conclusive report is the 2002 Public Health Assessment performed by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, a division of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention responsible for assessing public exposure to toxic substances. It analyzed the possible effects of contaminants known to have been found above EPA drinking standards in the base’s water system.

Even personnel on base before TCE and PCE were cleaned from the drinking water shouldn’t have been affected, according to the agency. The 2002 report acknowledged that six contaminants had been found at levels above the EPA’s drinking water standards but calculated that the amount and length of exposure was not expected to have led to illness.

The report used a “conservative” approach that assumed personnel would have consumed daily the highest amount of each chemical ever found in drinking water on the base. For TCE, that was 300 parts per billion, or 60 times the EPA’s standard of 5 ppb. For PCE, it was 91 ppb, or more than 18 times the EPA’s current standard.

Arsenic, lead, barium and a man-made chemical called 1,1-dichloroethylene also were analyzed after being found above EPA drinking water standards.

The report assumed military personnel would have been on the base a maximum of six years and drink two liters of water a day, and civilian workers for 30 years, consuming one liter of water a day. It also incorporated lower body weight for children who lived on the base.

After running the numbers based on EPA cancer risk models for each contaminate, the agency found that, with the exception of arsenic, none would be expected to cause more than one extra case of cancer in a million people, which is the EPA’s acceptable risk level.

For civilian employees, the agency found that an extra 1.4 cancers per 10,000 people would be expected due to arsenic. However, the report downplayed the findings, suggesting prior studies that established how much arsenic was safe to consume were flawed and didn’t match the situation at the joint reserve base.

“EPA classified arsenic as a carcinogen based on epidemiological studies where people consumed water containing 170 to 800 ppb arsenic for a 45-year exposure period. The maximum detected arsenic concentration in station wells was 22 ppb,” the report stated. “The study (also) failed to account for a number of complicating factors, including exposure to other non-water sources of arsenic, genetic susceptibility to arsenic, and poor nutritional status of the exposed population.”

The analysis also acknowledged that while some individuals may have been exposed to additional amounts of chemicals in soil and different water bodies on the base, that was not factored into its risk calculations.

“In these areas ... contaminant concentrations are below state and federal regulatory limits and below levels expected to result in illness or harm from exposures during recreational activities,” the report stated.

Lead was also found in the drinking water, the report stated. In 1985, it was detected at 20 ppb, higher than the EPA’s present drinking water standard of 15 ppb. Despite analyzing health risks for children who may have lived on the base for up to six years, the agency concluded that the 20 ppb lead level, along with levels of other contaminants, were not “expected to cause adverse health effects in adults or children.”

A spokesperson for the agency did not directly answer a question from this news organization about whether it would still come to that same conclusion today.

The spokesperson wrote in an email that the lead level of 20 ppb and arsenic level of 22 ppb were collected at an on-base supply wellhead, and not an exposure point such as a tap in on-base housing or work places.

“Given the distribution and potential mixing, it is difficult to estimate what the on-base personnel (including personnel and their families who resided on base for periods of time) were exposed to at the tap in the past,” the response stated.

In addition, the response noted, the Navy implemented measures to prevent exposures as soon as contaminants were detected in the supply wells.

Fourteen years later

In the 14 years since the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry released its analysis, toxicology experts say the science has been updated regarding some of the chemicals in question.

Dr. Perry Cohn, a retired environmental health epidemiologist in the Environmental and Occupational Health Surveillance Program at the New Jersey Department of Health, says the science has evolved in particular around arsenic and lead.

“Arsenic was probably downplayed too much back in 2002,” Cohn wrote in an email. “More recent evidence of health effects from low doses is stronger, though not yet totally consistent. Arsenic, like lead, may not have a totally safe dose.”

The level of PCE analyzed by the 2002 report also could pose a health risk, according to Cohn. Pointing to a 2009 study that appeared in the Environmental Health journal, Cohn says there is evidence that the levels of PCE analyzed in the federal report — 91 ppb — potentially could have affected the offspring of adults living or working on the base.

“Certain types of birth defects have been seen relatively consistently with PCE exposure from drinking water at levels below 100 ppb,” Cohn wrote.

In a 2005 report, the EPA offered new approaches to analyzing cancer risks for children. Applying those recommended methods, Cohn said he found that levels of TCE exposure would have led to an estimated cancer risk of about 1 in 10,000 for children who had lived on base from birth until age 6.

Those numbers aren’t particularly critical for the joint base; according to military documentation, the number of active duty personnel at the base peaked at about 1,500. Conservatively assuming each had two children and stayed on the base for six years, that would only amount to about two cancers between 1950 and when the contaminants were found in the 1980s.

However, there are other potential issues with the 2002 study, according to Cohn and other experts. For one, it didn’t account for personnel absorbing TCE and PCE through their skin or inhaling the vapors while showering.

“Showering is a route of exposure for (TCE and PCE),” Cohn wrote. “There have been decades of debate about how much. It depends on vent fans and opening windows during warm weather.”

Regardless, Cohn says that estimates of additional exposure from showering range from 50 percent to 200 percent of exposure through drinking water — meaning the 2002 analysis could have only accounted for a third of the exposure to chemicals for those living on base.

Asked why the 2002 report did not take into account combined exposure routes, an agency spokesperson stated that the agency “reviews environmental exposure information in a stepwise fashion.”

“Historical concentrations of TCE and PCE at the station supply wells were found to be below levels expected to cause health effects,” the response stated. “Therefore, ATSDR did not expect to see levels of concern when accounting for additional exposures via the dermal or inhalation pathways.”

Dr. Harry Milman, a consulting toxicologist and president of the consulting and expert witness firm ToxNetwork.com, also says that the health risks of TCE and PCE can be analyzed both separately and together, as they are similar chemicals that have similar health effects.

“This is different from combining the cancer risk of TCE and arsenic, for example, two very different chemicals whose exposure, absorption and health effects are significantly different,” said Milman, who worked for 18 years as a toxicologist for the EPA.

Analyzing TCE and PCE together would yield a higher risk than analyzing them separately, Milman said.

Taking another look

A review by this news organization of Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry studies conducted elsewhere found that the agency has applied these concepts during health assessments at other military bases. Perhaps the most well-known is an analysis conducted at Camp Lejeune, a Marine base located in Jacksonville, North Carolina, and the site of widespread drinking water contamination in the mid- to late-20th century.

An original agency analysis of Camp Lejeune, conducted in the mid-1990s, found no apparent health risks; however, it was later thrown out after the McClatchy News Service reported that a wealth of information on prior benzene exposures wasn’t incorporated.

As the Lejeune contamination received attention from lawmakers, the federal health agency began re-evaluating exposures at the base. The agency conducted health studies on former personnel and found elevated levels of cancers and other illnesses. In May, the agency released its draft of an updated public health assessment, which concluded exposures to benzene, TCE, PCE, vinyl chloride and other chemicals had been at levels high enough to affect the health of personnel.

The study combined the effects of inhalation, skin contact and ingestion, and also analyzed the risks of TCE and PCE together, said Dr. Nachman Brautbar, an internist and nephrologist who specializes in toxicology and has consulted on cases from Camp Lejeune. That’s important, he explained, because personnel not only were exposed to the contaminated water during work, but they also drank it, breathed it in and absorbed it through their skin during showers at home.

“So you had essentially triple exposure (at Lejeune). You have skin absorption, inhalation and ingestion,” Brautbar said.

The Lejeune report stated that pairing of the TCE and PCE was based on science the agency updated in 2004 — two years after analysis had concluded at the joint reserve base in Willow Grove without looking at combined effects.

Asked about the discrepancies between the two reports, a spokesperson for the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry wrote that the 2004 document did update the agency’s approach for combining TCE, PCE, and 1,1-dichloroethylene exposure.

“PCE and TCE may be additive for neurologic effects, but slightly inhibitory for liver and kidney effects,” the response stated. “ATSDR considers an additive approach for these chemicals to be conservative.”

In addition, the 2002 joint base health assessment did not take into account any exposures to PFOS and PFOA. Though unregulated, the chemicals have caused alarm in the region after being found in local public and private water wells above safety levels recommended by the EPA.

In 2014, testing by the military of the Horsham Air Guard Station drinking water found concentrations of 11.9 ppb for PFOS and 3.28 ppb for PFOA. Combined, those levels are 216 times higher than the EPA’s recommended limit of 0.07 ppb for drinking water.

By contrast, levels in the most contaminated area public well, in Warminster, reached 1.43 ppb combined, more than 10 times lower than the air guard station. Customers in Warminster also likely benefited from water being diluted by other, non-contaminated wells hooked into the system before reaching their taps.

Rob Bilott, an environmental attorney who has been writing to the EPA for years detailing the dangers posed by perfluorinated compound contamination nationwide, said he wasn’t aware of any drinking water system in the country that has had PFOS levels higher than the air guard station.

The exposure there could have taken place as far back as the early 1970s, when use of the firefighting foams that contain the chemicals began, and continued until 2014, when all water on the base was deemed unsafe to drink.

The spokesperson for the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry wrote that it is conducting a new public health assessment to evaluate PFOS and PFOA exposures near the base, which was previously reported by this news organization.

However, that study will evaluate “public health implications,” in “offsite public and private drinking water sources,” the response stated, making no mention of former on-base personnel.

A month after Nicole Woxland’s husband, Wade, was diagnosed with bladder cancer in July 2012, a doctor told them it was likely the former flight engineer had been exposed to something that caused his illness.

Thinking the cancer, which eventually took her husband’s life, might be linked to his 20 years in the U.S. Navy Reserve, including 3½ at Willow Grove Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base, Woxland submitted a letter from the doctor with a claim for benefits to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs in October 2012.

Woxland still doesn’t know to what her husband was exposed, but while he was battling his illness she repeatedly tried to get the VA to approve service-connected benefits — to no avail, she says.

It’s a familiar struggle for former personnel — and their family members — who say a lack of communication from the military about potential prior exposure has left them on their own to navigate a VA process they find confusing. In some cases, veterans and civilians who worked on the Horsham base say they were unaware of potential exposures until connecting with others on social media.

Others say their concerns about past contamination of toxic chemicals found in the base’s soil, groundwater and drinking water have fallen on deaf ears. And now they say, the media, lawmakers and regulators are focused on the risks to nearby communities, not those who served and worked at the base.

“Where’s our letter? Where’s our notification saying, hey, as a precaution, why don’t we send you to the VA and we’ll set up a screening clinic?” said Paul Lutz, a veteran and vocal member of a Facebook group that Woxland started to help former personnel facing similar situations. “It’s unbelievable.”

As Wade Woxland’s health deteriorated, so did the couple’s hope the VA would recognize his illness was linked to his service.

“It was a (expletive) show. They kept asking for more records,” she said.

Woxland, who lives in Omaha, Nebraska, says doctors removed Wade’s bladder and made one out of intestinal tissue. Then the cancer spread to surrounding lymph nodes, the stomach and other areas.

“We went to Hawaii and redid our wedding vows” in fall 2013, she said. “When we came back, (the cancer) had basically spread everywhere.”

Wade lived three more months and died Dec. 28, 2013, at age 49. In addition to his wife, he is survived by their three children: 19-year-old twins Garett and Connor, and 17-year-old Jakob, all born at Abington Memorial Hospital when Wade was stationed at Willow Grove.

″(Wade) had tumors in his legs and groin when he was in hospice,” his wife said. “It was everywhere.”

Woxland says her family used TRICARE, a health benefit program for veterans and their families, that covered a great deal of the costs of Wade’s illness. But they still ended up on the hook for about $50,000 from both traditional and alternative medicine therapies.

A month before her husband’s death, the VA denied the initial claim for benefits, Woxland said. She didn’t give up. Instead, she reached out to an independent consultant with experience helping veterans organize and submit medical claims. For about $8,000, the consultant had Wade’s records reviewed by another independent doctor and helped re-open the claim for benefits and submit new documentation.

“The VA sets you up for failure, unless you know somebody who knows the system,” Woxland said. “It was the best decision I ever made.”

In July 2015 — a year and a half after his death — the service connection claim was approved, Woxland said. The family was retroactively awarded 100 percent disability compensation for the duration of Wade’s illness and funeral expenses. Woxland also began receiving more than $1,000 a month in compensation, which she will receive for the rest of her life if she does not remarry.

Woxland said the VA conceded in its approval letter that her husband was exposed to contamination because of Willow Grove’s designation in 1995 as a Superfund site.

But a VA spokesperson said the department is “unaware of any significant past or current exposure issues” at the now-closed base and the adjacent Air Guard Station, which is still in operation.

Woxland fears telling her story might result in the compensation being revoked. But she says it isn’t about the money, it’s about continuing a struggle for answers her husband began.

“He was the most compassionate person you’d ever meet,” Woxland said. She said she wondered if her husband would have been better off forgoing treatment. “He realistically should have just said, I’m done. I want to live as myself. But he suffered months of severe vomiting, weight loss and pain, because he didn’t want anybody else to have to go through it.”

But others are going through it, says Lutz, who worked as a flight engineer at Willow Grove from 2000 to 2012 and now has multiple myeloma, which the VA has recognized is connected to his service. But he feels as though former personnel are on their own with the public’s attention focused on the health of residents who live near the base.

“Everything you see is civilian-based,” Lutz said. “If it’s in the water around town, it’s in the water on the base.”

Woxland started the private Facebook group, NAS JRB Willow Grove Cancer Diagnosis, in March 2013 to help other former personnel also struggling for answers. The group’s aim is to disseminate information to those who were stationed at the base and now have cancer or other illnesses “that are possibly related to the contamination of water, soil and other (environmental) factors at the base.”

Gregory Preston, director of the Navy’s Base Realignment and Closure Program Management Office East, says he knows that former personnel are sharing their concerns over social media.

“Military and civilian workers at the former NAS JRB Willow Grove have raised concerns about the quality of drinking water during their stay, or tenure on the installation prior to its closure. They are encouraged to consult their health care provider with questions about health concerns,” according to Preston.

Preston and communications officers at the Air Guard Station say there’s no automatic process in place to alert those who served there about potential health concerns.

Lt. Col. Jacqueline Siciliano, an environmental manager at the Air Guard Station, says personnel are given copies of the public drinking water notice about perfluorinated compounds when they leave, so they can place it in their medical file. Master Sgt. Chris Botzum, public affairs representative, says the air guard station also has reached out to past personnel during luncheons and reunions.

“Word is getting out via our retiree organization,” Botzum said.

Preston says he is not aware of efforts by the Navy, or any systematic process that could notify former personnel of potential exposures.

While the VA does not yet have a system in place to add new information about proven or potential exposures to service members’ medical records, it is in the early stages of developing one with the U.S. Department of Defense, a VA spokesperson said. The system, known as the Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record, will capture “all available service-related exposure information for the duration of an individual’s military service,” the spokesperson said.

The system also could potentially fill a gap in the VA’s ability to track personnel by service at a particular base or with common deployments or exposures, the spokesperson added. Currently, it’s only possible in cases where “special exposure scenarios” have been identified, such as through registry programs for veterans who may have been exposed to Agent Orange.

Lisa McKraken, of McMinnville, Oregon, who served at Willow Grove, says she never received any formal notice or heard from anyone about potential exposures at the base. She thought it was odd when she started hearing from her former colleagues about others who were becoming ill. “I was like, OK, this is a small base, what on earth is going on here?” she said, noting that it seemed like a lot of people.

She left the Navy as a petty officer second class after she was diagnosed with breast cancer in October 2004 at age 34. She had completed 3½ years in the service when she arrived at Willow Grove. About 18 months later, an on-base doctor found a lump in her breast during an annual exam.

“I was still on active duty; I was right in the middle of my tour,” she said, adding she was automatically approved for service-connected benefits for that reason.

If it weren’t for Facebook and social media connections, she says, she never would have found out there are hundreds of others wondering if potential exposures at the base could have made them ill.

“There’s no way I would have connected the dots had I not heard and found out that so many people that I served with are either sick or dead,” she said.

Now cancer-free for 11 years, McKraken considers herself one of the lucky ones, but she still worries about what she might have been exposed to. She worked in aviation maintenance administration, keeping the logbooks and data for the aircraft. It was an in-office job but she says she swam on the base, showered there and drank the water.

“You’ve gotta flip a coin,” she said. “Who knows?”

“Think of all the people that aren’t even on Facebook,” said Lutz, comparing the situation to Camp Lejeune, a Marine base in North Carolina where the military admitted after decades that drinking water contaminated with TCE, PCE, benzene and other chemicals sickened personnel. “It took (former personnel of Camp Lejeune), what, 20 years for them to start getting settlements? How many (Willow Grove) people won’t even be here anymore?”

Lutz says it’s not about the money, either, although he adds he wants to know his family will be taken care of if he loses his battle with multiple myeloma. At the least, he says, the Navy acknowledging contaminants on the base made personnel sick might prevent the same thing from happening again in the future.

“Maybe it’ll stop the government from doing what they know is wrong,” Lutz said.

“They know it. They know it’s wrong.”