'On their radar screens'

This story was first published on Nov. 19, 2017.

By 1995, U.S. Department of Defense employees knew firefighting foams used across the country could potentially contaminate drinking water sources with perfluorinated chemicals, according to documents reviewed by this news organization. But no drinking water supplies, including those in Bucks and Montgomery counties, were tested until nearly two decades later.

During that time span, various studies linked the chemicals to a variety of health effects, including developmental issues in children, high blood pressure, ulcerative colitis and some cancers.

The documents push back when personnel first expressed concerns about potential drinking water contamination from 2001, the year initially identified in documents reviewed during our ongoing investigation. Other newly reviewed documents show additional concerns about the foams continuing into the early 2000s.

In summer 1995, an article titled “Foam and the Environment: A Delicate Balance” appeared in the official journal of the National Fire Protection Association, a trade organization that creates national standards and codes for firefighting equipment and protection.

Among the listed authors are Robert Darwin and Joseph Gott — both “with the U.S. Department of the Navy,” the article states — as well as Christopher Hanauska, an employee of Hughes Associates (now Jensen Hughes), the military’s primary contracting firm on firefighting foam issues at the time.

The article reviews numerous environmental issues resulting from the use of firefighting foams at facilities “throughout the world.”

“They have undoubtedly saved lives, reduced property loss, and helped minimize the global pollution that can result from the uncontrolled burning,” the article states. “However, the fire protection community has become concerned about the potentially adverse impact of foam discharges on the environment, particularly those that reach natural or domestic water systems.”

Most of the article addresses the effects of firefighting foams on wastewater treatment systems, as the foams were already known by that time to paralyze treatment plants. But the article also expressed concerns regarding the foams’ “fluorochemical” ingredients, known today to include the toxic substances PFOS and PFOA.

Such ingredients “are known to not fully biodegrade,” the article states, meaning that “if allowed to soak into the ground, those that don’t become bound to the soil may eventually reach groundwater or flow out of the ground into surface water. If they have not been adequately diluted, they may cause foaming or remain harmful.”

The article then references drinking water concerns.

“It is prudent to evaluate the drinking water supply if a foam discharge has contaminated it and to use alternative water sources until you are certain that (chemical) concentrations no longer exist,” it prompts, adding that the chemicals “may have an affinity for living (organisms).”

The article was published 19 years before the military first tested drinking water near former military bases in Bucks and Montgomery counties for the chemicals. Resulting investigations led to the closure of 16 public drinking water wells and more than 200 private wells in Warminster, Warrington, Horsham and surrounding communities because of high levels of PFOS and PFOA. Similar drinking water contamination has now been found at 45 U.S. military bases around the world, all of which were only tested in recent years.

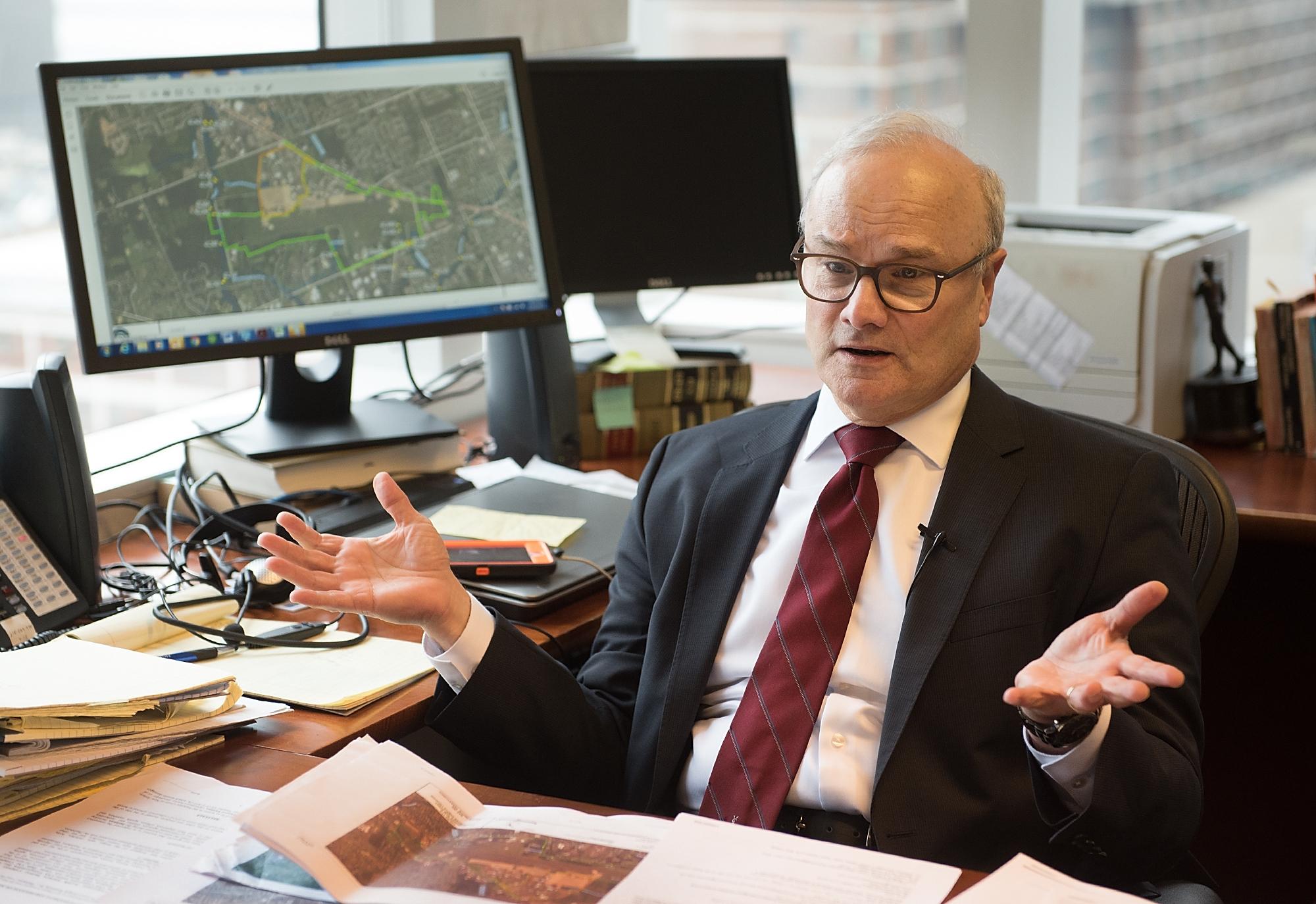

The 1995 article and other documents reviewed by this news organization were provided by the Cuker Law Firm LLC, a Philadelphia firm that obtained them through an ongoing lawsuit against the federal government. Attorney Mark Cuker said his review of the documents led him to believe the military was “willfully ignorant” of the hazards of foam — and did not take action.

“They were having meetings, this was way up on their radar screen,” Cuker said. “But no one really took charge, no one took the bull by the horns. ... And obviously people exposed (locally) are drinking that water all this time.”

This news organization reached out to the Department of Defense with questions about the documents referenced in this story on Nov. 8. Responses were not received as of Friday afternoon.

‘Potential toxicity to humans’

In the years following the 1995 article, other documents reviewed by this news organization show military personnel continued to acknowledge firefighting foam hazards.

In March 1997, the Naval Research Laboratory sent a “status report” on firefighting foam to the commander of Naval Air Systems Command, a Navy program tasked with designing and supporting the department’s aircraft, weapons and systems.

In a section titled “environmental issues,” the report listed “persistence and biodegradability of chemicals ... including potential toxicity to humans.”

The report noted that environmental tests for foam contamination were primarily focused on risks to wildlife at the time; large amounts of foam could potentially eat up oxygen and suffocate aquatic life as the foam broke down. However, the report noted foam ingredients such as PFOS “apparently” do not break down naturally, presenting long-lasting risks.

“If non-biodegradability concerns are based on the persistence of (perfluorochemicals), then the environmental impact tests currently used to assess foams do not address this concern,” the report stated.

Additional records show some military programs experimented with ways to measure the amount of perfluorochemicals leftover after foam use, and potentially limit their release into the environment.

In 1996, a report co-authored by the Navy’s main research laboratory and employees of Hughes Associates assessed a piece of machinery called a “separator” that could skim off a frothy layer of foam from firefighting wastewater.

They measured success using a rudimentary “drain time” test: the faster the remaining wastewater drained, the less perfluorochemicals it was thought to contain. They also tried a second method using other chemicals that would visually react with the perfluorochemicals. Despite some “promise” of the tests, there’s no evidence they were used on a wide scale.

By 1999, water at some military bases had been analyzed using much more sophisticated techniques.

In a study published that year, researchers from Oregon State University, with funding from the Environmental Protection Agency, reported that they used special imaging equipment to detect the perfluorochemicals in groundwater beneath three bases where they looked: Naval Air Station Fallon in Nevada, Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida and Wurtsmith Air Force Base in Michigan.

It was confirmation that the foams were releasing chemicals into the environment. Yet, there’s no evidence of any wider effort by the military to use similar technology to begin testing other bases or water supplies until after 2010.

On a photocopy of the Oregon State study in the military’s records obtained by Cuker’s firm, someone had scribbled, “What is significance of findings? Is this a bad thing?” A second, handwritten note answered: “Significance is it was funded by EPA. Indicates their (sic) getting interested in (firefighting foam).”

In 2013, the EPA began testing water utilities around the country for the presence of PFOS, PFOA and related chemicals. In November of that year, they found the chemicals in Warminster’s public water, followed by Horsham’s water in June 2014.

That summer, the water supply at the Horsham Air Guard Station was tested by the military for the first time and was found to contain extremely high levels of the chemicals. It would become the first of many: The military now is testing each of its more than 500 water systems.

'Waiting for news about toxicity'

Other newly examined records show that despite the early concerns, some military personnel in the early 2000s held off taking action on firefighting foams until toxicity concerns were confirmed.

In a November 2001 email, Navy contractor James Hill wrote to the Navy’s Doug Barylski, who other emails identify as one of the department’s primary experts on firefighting foams. Hill asked Barylski to review an email he was going to send to a third person, Jeff Fink, a manager in the Navy’s aircraft carrier program. Fink had previously said in an email he believed firefighting foam issues “could be on the magnitude of asbestos elimination.”

Hill’s proposed email to Fink stated, “The (firefighting foam) sky is not falling — yet,” and it noted the EPA “cannot ban” foams under its main toxic chemical law. While chemical company 3M announced a year earlier that it would phase out production of its PFOS-based foams, Hill noted other companies produced similar foam using a different chemical process. Even if those foams turned out to be problematic as well, Hill stated, the Navy still would have time to react.

“If something is discovered about the other brands or EPA starts to push for regulations ... there appears to be 3-5 years of lead time to come up with a plan,” the proposed email stated.

A 2003 email chain revived the concerns during the planning of an overhaul of the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson, with one Navy employee writing, “Where does the issue stand now? Do we need to address it ... or did it just go away?”

Barylski responded that it was “old news,” reiterating that only PFOS-based foams were affected. Barylski further predicted that because perfluorochemicals had a wide array of uses across multiple industries, any wide-scale phaseout would primarily be a problem for “the DuPonts of the world.”

“Industry will not make any shift until there is proof of toxicity issues,” he predicted. “But there is no environmental regulation change at this point, and none about to come out. Let’s at least wait to push the panic button until we have some additional news about toxicity.”

Records from about the same time show the Navy wasn’t the only branch of the military that considered taking action. In a PowerPoint dated Oct. 16, 2001, and credited to “Headquarters U.S. Air Force,” Air Force personnel played out potential future restrictions on firefighting foams.

The presentation noted that the Air Force “worked with” the Navy, EPA and foam manufacturers to develop a timeline for a potential foam phaseout, noting that “regulatory restrictions would take roughly 10 years to begin to restrict availability.”

“The Joint AF/Navy position is that we can expect unlimited availability of (foam) until the years (sic) 2010,” the presentation continued. “Future after that date is open to scientific and political pressures.”

Records also show talk of concerns and regulations extended beyond the military and into civilian aviation.

In a report for the Federal Aviation Administration conference in May 2002, Hughes Associates recommended the industry reassess how it stored, handled and discharged foam, which the military contractor said was used at the 24 largest U.S. airports.

“Even if the disposal guidelines recommended by most foam manufacturers are followed (controlled input to a wastewater treatment plant), this will not change the fluorocarbon ... impact as they pass through the plant into the watercourse,” the report stated.

A section of the report referencing efforts by the EPA was telling, demonstrating knowledge that foam use could expose humans to PFOS.

“The EPA has identified the release of (chemicals) in foam ... to the water as one of the possible routes of human exposure for PFOS,” the report stated.

The report stated the EPA also told DOD fire and emergency personnel that “a program to seek, test, and consider long-range alternatives to current fluorosurfactant-based (foams) would be prudent.”

No changes until ‘crisis’ hits

Additional records show some military programs considered such actions.

The 1997 report on the “status” of foams noted concerns that they would “eventually” become targets for regulators. The report identified potential solutions such as using alternative foams or water during firefighting training exercises, and reducing the quantity of perfluorochemicals in the foams. But “the development of a new firefighting agent, an environmentally benign foam, offers the most attractive solution,” the report concluded.

In 2001, Naval Air Systems Command put out a development plan for a foam alternative. It made several recommendations: define “environmentally friendly,” conduct a cost/benefit analysis of swapping foam stockpiles, analyze how best to dispose of foams, and consider potential short-term “best practices” to limit release of foams into the environment.

In an email the same year, the Navy’s Barylski also wrote to colleagues that “we should obtain research funds” during the military’s budgeting proposal process “to begin getting into the (foam) environmental issues before it becomes a crisis.”

In a 2003 email, Barylski wrote he had followed up and “submitted issue papers to look at (foam) alternatives, considering it prudent to do some early work.”

“But without any crises, the papers have not been funded,” Barylski stated.

In fact, it appears more than a decade passed before actions mulled by these various programs were put into effect. In 2015, after major contamination was uncovered in Pennsylvania, New Hampshire and other states, the Department of Defense finally called for proposals to develop a firefighting foam free of perfluorochemicals.

This year, the department awarded $2.5 million for three research projects, with anticipated completion dates in 2020, according to a recent U.S. Government Accountability Office report.

In 2016, following the release of new EPA safety advisories for both PFOS and PFOA, “military departments issued policies restricting the use of firefighting foam at their installations,” according to the GAO.

The policies came 19 years after the 1997 Navy report noted that perfluorochemicals in firefighting foam don’t break down in the environment and may be toxic to humans, and 15 years after the 2001 development plan and other records of that time recommended foam users reduce or eliminate discharges.

The delay in restricted use policies was costly.

In 2011, Robert Darwin, an ex-Hughes Associates employee, delivered a report that estimated the military’s inventory of PFOS-based foams.

Between 2004 and 2011, Darwin wrote, the military used an estimated 1.05 million gallons out of an original supply of 2.1 million gallons of the PFOS-based foams. Darwin added that he was “unable to find any evidence” of foam disposal via incineration.

Instead the foams ended up “highly diluted in surface waterways, in subsurface water, absorbed into the ground, or partially evaporated,” he wrote.