Taking a closer look

This story was first published on Sept. 18, 2016.

Mary Onufrey doesn’t put much stock in what “they” say anymore.

“I don’t believe them,” the 70-year-old Warminster resident said of military and government officials when asked about a recent study on cancer in the area by the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. “I think they are trying to get themselves out of deep trouble.”

The federal agency, an arm of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, together with the Pennsylvania Department of Health, studied nearly 30 years of data on seven types of cancers in three ZIP codes, after the unregulated chemicals perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) were found in recent years in drinking water in Warminster and nearby Horsham and Warrington.

The three communities surround the former Naval Air Station-Joint Reserve Base Willow Grove, the current Horsham Air Guard Station and the former Naval Air Warfare Center, and the military has acknowledged the source of the PFOA and PFOS is likely firefighting foams used on the sites as far back as the early 1970s.

Many area residents hoped the study would provide them with answers about the contamination and their illnesses, but they were only left with more questions after the ATSDR said the results were “inconclusive” and the area didn’t meet the CDC’s definition of a “cancer cluster.”

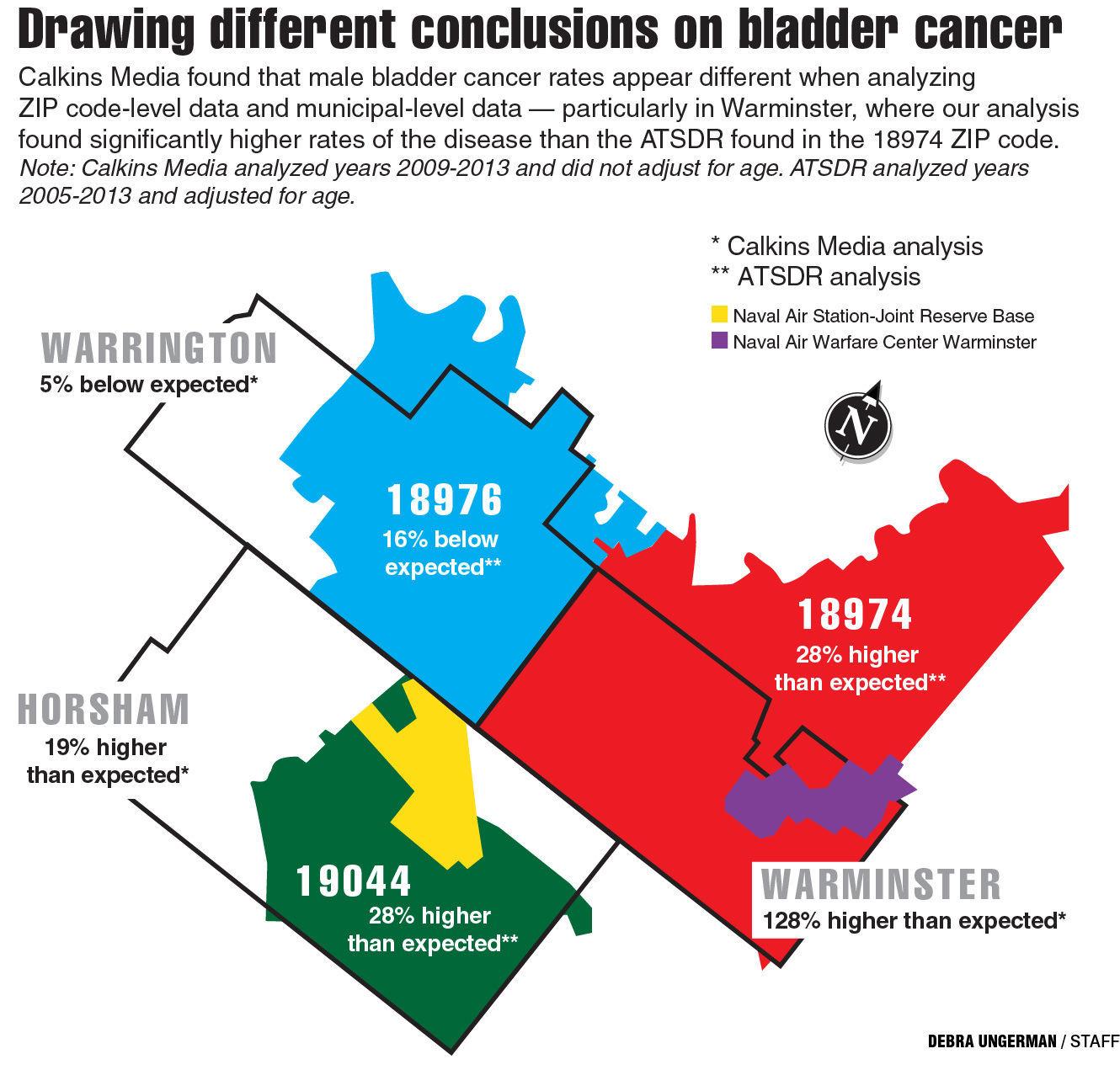

This news organization decided to take a second look. Our findings suggest some of the methods used by the ATSDR may have missed what appear to be abnormally high rates of some cancers — particularly bladder cancer — in the affected communities.

The results also could help explain why residents like Onufrey, who lives on Spencer Lane, find it hard to believe there aren’t unusual amounts of cancer in their neighborhoods.

“What does it take to make a cluster, when you have this many people on one block (who have had cancer)?” Onufrey’s sister, Elizabeth Beaver, of Northampton, asked. Onufrey said she knows of at least 19 people in her neighborhood, including herself and her late husband, who have had various types of cancer.

Onufrey’s doctor said she was diagnosed with stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2000. In 2001, her husband, Stephen, was diagnosed with throat cancer. Onufrey’s lymphoma returned in 2006, and two years later, she developed lung cancer. Then, in 2013, her husband was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He died in June 2015. The couple’s two daughters no longer live in Warminster, but they both have thyroid diseases.

No doctors or health officials have ever told the family members that studies have linked some of the diseases they’ve developed to the chemicals. Onufrey smoked, but she still wonders about the water. She started buying bottled water, just in case.

“I just wish they would fix this. I’m not looking for a lot of money, or any money. I think I should be able to drink my water; I think I should be able to cook my food; I should be able to shower without having to worry about it,” Onufrey said.

A careful reading of the ATSDR report shows the agency isn’t drawing any concrete conclusions. The very first sentence of the document states, “This cancer data review provides an inconclusive picture of cancer incidence rates in Horsham, Warminster, and Warrington ZIP codes.”

Deeper in the report, the agency lays out the what it calls the “limitations” of such a study:

- It can only examine the correlation to cancer rates, not the cause. In other words, it can’t prove the chemicals led to the cancers, even if the rates are high.

- ZIP codes may not be the most accurate way to analyze the affected populations.

- People moved in and out of the examined areas over the 30 years reviewed.

- The study didn’t incorporate other important factors, such as the occupations and lifestyles of area residents.

"(The report) was a simple analysis,” Perry Cohn, a retired environmental health epidemiologist for the New Jersey Department of Health, wrote in an email to this news organization.

Cohn said that because it didn’t actually involve interviews with residents to learn their histories, the analysis likely lumped together two groups of people: those living close to contaminated wells, who presumably had more of the chemicals in their water; and those who did not.

“Occupational exposures from working on the bases was not analyzed separately,” Cohn continued. “The effect of individual factors, like smoking and residential histories, can only be analyzed with interview data from all subjects.”

Bruce Alexander, a University of Minnesota environmental health sciences professor who has conducted health studies on people exposed to PFOS, warned against drawing any conclusions from cancer-cluster studies, referencing the statistical rule that correlation does not equal causation.

“It’s always important and interesting,” Alexander said of studying cancer data. “But drawing conclusions without fully understanding the populations being compared should be done very carefully.”

A second look

To develop a more complete picture, this news organization explored the limitations of cancer-cluster studies and independently analyzed state cancer data from 2009 to 2013 — the five most recent years available.

The state doesn’t publish ZIP code-level data, but we reviewed municipal-level data for 11 cancers some studies found may be linked to PFOA and PFOS. We didn’t adjust the cancer rates to account for age differences the way the ATSDR did, so the analysis cannot be compared apples to apples. However, it still offers insights.

Most strikingly, the municipal-level cancer data appeared to suggest populations living closest to the contamination had higher rates of bladder cancer, a relationship that may have been diluted by the ATSDR’s use of ZIP codes rather than townships in its review.

Compared to the state average, the agency found bladder cancer rates were 18 percent higher than expected for men in the three ZIP codes combined between 2005 and 2013, although they were 10 percent lower than expected for women. It also found the bladder cancer rate for men was 28 percent higher than expected in 18974 (Warminster), 28 percent higher than expected in 19044 (Horsham), and 16 percent lower than expected in 18976 (Warrington) during that period.

The picture of bladder cancer changed when this news organization reviewed township level data, and was much worse for Warminster. Between 2009 and 2013, the township’s bladder cancer rate was the highest of any municipality in the county — in fact, it was more than double the state rate.

In the five years reviewed, 113 of Warminster’s approximately 32,000 residents were diagnosed with the disease. That’s more than the 102 cases diagnosed in Bensalem, which has a population of more than 60,000 residents — nearly double Warminster’s.

A total of 105 of the 113 Warminster cases occurred in people over 60, the data showed. But even in that age group, the rate was 78 percent higher than the state rate for people over 60, which is 62 cases per 10,000 people.

The same was true for younger people. From 2009 to 2013, five Warminster residents under 50 developed bladder cancer; a rate nearly three times higher than the state rate for the same age group. Using the state rate, only one or two cases would have been expected.

Also notable in the ATSDR report was that the 18974 ZIP code covers not only Warminster, but large sections of Warwick and Northampton as well. While Northampton has two groundwater wells with very low amounts of PFOA, Warwick’s water system doesn’t contain any PFOA or PFOS. If the chemicals in Warminster’s water are a cause of higher than expected rates of bladder cancer, that could explain why the disease appears to occur at a higher rate in Warminster than in the larger 18974 ZIP code.

In Horsham, the opposite was found. The 19044 ZIP code is smaller than the township — the C-shaped area cradles the naval air station and includes the township’s most contaminated wells. At the same time, the northern corners of Horsham aren’t part of the ZIP code, so neither are some of the areas farthest from the contaminated wells.

It makes a difference: the more compact ZIP code appears to have a higher bladder cancer rate than the entire township. While the ATSDR found bladder cancer rates were 28 percent higher than expected for men from 2005-2013, the number decreased to 19 percent in this news organization’s analysis of the larger township.

Another limitation of the ATSDR’s analysis of ZIP codes is that it didn’t analyze adjacent communities where the chemicals have been found at lower levels. Left out were 19040 (Hatboro) and 19002 (Ambler to Horsham).

“We really wanted to focus in this review on the most concentrated, the most-known, highest-contaminated areas in the hope that (if there is an association), that’s where you’ll see it,” Sharon Watkins, director of the Pennsylvania Department of Health’s Bureau of Epidemiology, said at an August community meeting.

But some nearby towns also appear to have elevated rates for certain cancers.

In Hatboro, recent test results show the chemicals are present in five of seven drinking water wells, although the levels are below the EPA’s recommended 70 parts per trillion advisory limit. The seven wells account for more than 70 percent of the borough’s drinking water.

This news organization’s analysis found the bladder cancer rate in Hatboro was 55 percent higher than the state rate between 2009 and 2013, and it was 88 percent higher than the state rate among residents over 60.

In Upper Southampton, residents are still waiting to find out the results of tests on two wells that supply about 20 percent of the township’s water and are located close to the Warminster border. The other 80 percent of water is purchased from the Bucks County Water and Sewer Authority and doesn’t contain the chemicals at any detectable level.

According to our analysis, bladder cancer rates in Upper Southampton are about 55 percent higher than the state rate, although more than a quarter of the town’s residents are 60 or older — one of largest senior populations in Bucks.

Victoria Francis, of Upper Southampton, isn’t a senior, but she’s a heavy water drinker.

“I’m not a coffee (or) tea drinker. I don’t drink juice. I drink water,” she said. “Everybody laughs at me. I probably drink about a gallon of water a day.”

But the 51-year-old stopped drinking from the tap and began buying bottled water in the mid-1990s, after she heard rumors in the neighborhood that the base was closing and chemicals were being dumped. Her home on Hilltop Road is just a few thousand feet from the former warfare center and Upper Southampton’s public wells.

She is quick to say she doesn’t know what made her sick, but in 2014, she was diagnosed with bladder cancer and a kidney tumor that doctors told her was caused by some type of chemical. The cancer later spread to her lungs, but this month Francis found out she is in remission after undergoing experimental immunotherapy treatment, according to her medical oncologist at Penn Medicine, Dr. David Vaughn.

When asked about the cause of Francis’ tumor, Vaughn said there seems to be a correlation between certain organic solvents and bladder cancer, but it’s not as strong as between tobacco and the disease. However, Francis has never smoked.

High rates of bladder cancer aren’t present in other neighboring towns where testing has shown no widespread water contamination. In Warwick, the bladder cancer rate was 26 percent lower than the state rate; in Northampton, it was at about the state rate; and in Upper Moreland, it was 5 percent lower than the state rate.

Asked why ZIP codes were used instead of townships, the ATSDR said it’s “typical” for an agency such as the Pennsylvania Department of Health — which assisted with the cancer cluster analysis.

“Data at the municipal level often do not include enough cases of rarer cancer types for analysis,” Cristina Cope, health communications specialist with the CDC, wrote in an email.

Smoke screen

Alexander, the University of Minnesota researcher who’s studying PFOS and bladder cancer, sees complications in analyzing the disease.

“Bladder cancer is not that uncommon,” Alexander said, adding that it was one of the first cancers “linked to environmental exposures, particularly workplaces and smoking rates.”

Pennsylvania doesn’t track smoking rates, so it couldn’t incorporate that data into the ATSDR cancer cluster study, but other states have done so.

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment recently completed such a study in El Paso County, about an hour’s drive south of Denver. Water supplies there serving about 90,000 people have been contaminated by PFOS and PFOA.

That state department’s population analysis found elevated rates of lung cancer (66 percent higher than expected), kidney cancer (17 percent higher), and bladder cancer (34 percent higher). Using state data on obesity and smoking, however, researchers were able to calculate the higher rates of lung and kidney cancers could likely be attributed to lifestyle factors.

That wasn’t the case for bladder cancer. The Colorado study found bladder cancer cases in the affected area were less likely to be caused by obesity and smoking than the bladder cancer cases in the unaffected areas of the county.

It also found the highest percentage of cases in residents ages 65 to 74 (56 percent higher than expected), followed by residents ages 55 to 64 (42 percent higher). Men also appeared to develop bladder cancer at a much higher rate than women, which mirrored bladder cancer rates in Bucks and Montgomery.

Alexander said part of the problem when trying to find a link between the chemicals and bladder cancer is that PFOS hasn’t been studied as much as PFOA and PFOS is the primary contaminant around the local bases and in El Paso County.

“PFOA was manufactured in more places,” Alexander said, adding that makes it easier to find and study workers who had significant exposures.

However, some studies, including those conducted by Alexander, have found some associations between PFOS and bladder cancer. While studying workers at a 3M plant that manufactured PFOS in Decatur, Alabama, Alexander noticed three had died from bladder cancer — more than would be expected, given the size of the workforce.

But when his team began counting the number of employees with bladder cancer diagnoses, the numbers didn’t support their earlier finding. Alexander said he’s in the midst of further research on cancer rates at the plant.

Looking back

In Bucks and Montgomery counties, there’s also the issue of time. If PFOS does cause bladder cancer or other illnesses, one would expect to see steadily increasing rates of the diseases over time, since firefighting foams have been used on the military bases since the early 1970s.

This formed the basis of the ATSDR’s review of three decades of data: 1985 to 1994, 1995 to 2004, and 2005 to 2013.

But the ATSDR cancer-cluster report found there were no conclusive patterns.

While the bladder cancer rate for men in the Warminster ZIP code did steadily increase in each decade reviewed, it decreased for women. And bladder cancer rates for both genders in the Warrington and Horsham ZIP codes offered no discernible patterns: rates were below average, decreasing, or inconsistent over time.

But, again, the ATSDR’s study is limited, in that it didn’t incorporate any data on when potential exposure to PFOA and PFOS began in the different ZIP codes, or the extent of the potential chemical exposure.

By reviewing data provided by the three water authorities, this news organization was able to build a basic picture of how much water was being provided from the area’s most contaminated wells prior to their closure in 2014.

The three water systems rely heavily on groundwater wells located throughout the townships for their drinking water. Water from each well blends with water from others as it moves through the system, meaning residents could expect to receive a portion of their water from each well, based on their location and how much water is pumped from each well.

Warminster appears to have been most affected.

At their highest readings, the township’s three most highly contaminated wells, which were taken offline in 2014, each had more than 200 parts per trillion of the chemicals. Well 26 measured 1440 ppt at its peak, while wells 10 and 13 topped out at 280 ppt.

Each well was drilled by 1972. In 2013, the three wells contributed about 558,000 gallons of water daily, or about 19 percent of the system’s 3 million gallon daily demand.

The wells are close to the former warfare center and one another, meaning nearby residents could have received a great deal of contaminated water before it was blended with other wells. Because the wells were all operating by 1972, residents there could have been exposed since then.

There could have been less exposure in Horsham, where there were two highly contaminated wells, each at opposite ends of the naval air station. The most contaminated was Well No. 40, which contained as much as 1,063 ppt of the chemicals. It wasn’t operational until 2001, so the exposure time may have been less than in Warminster. The other well, which contained as much as 990 ppt, was drilled in 1980, according to records provided by the water authority.

In 2010, the last year both wells operated for the entire year, they combined to produce about 367,000 gallons a day, or about 15.6 percent of the town’s supply, according to Horsham Water and Sewer Authority records. That’s about 200,000 gallons less per day than the highly contaminated wells in Warminster were contributing to Warminster’s system.

But could the differences potentially explain different cancer rates? Warminster does appear to have higher rates of cancer: the ATSDR found two cancers were significantly elevated for Warminster men in the last decade reviewed: bladder and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In Horsham, the ATSDR found, no cancers were statistically elevated in that time period.

Notably, the ATSDR report does show rates for a number of cancers increased some time after well No. 40 was placed into service in 2001. Between 1995 and 2004, Horsham men were diagnosed with bladder cancer at a typical rate, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma at a rate 25 percent lower than expected. From 2005 to 2013, bladder cancer rates for men increased to 28 percent higher than expected and non-Hodgkin lymphoma rates to 36 percent more than expected.

Warrington presents a different situation.

That township’s water customers are split: about two-thirds are in the eastern district, which relies on well water that was subject to contamination. The other third are in the western district, which receives all of its water from the North Wales Water Authority, and has no PFOS or PFOA contamination. Compounding the problem, the 18976 Warrington ZIP code also pulls in sections of neighboring Doylestown Township and Warwick.

The amount of highly contaminated water being pumped into the Warrington system also appears to have been lower than the amount in Warminster. Warrington’s three highly contaminated wells blend at a single entry point of the system. In 2013, they provided an average of 296,000 gallons a day, or 14 percent of the township’s supply. Averaging the highest levels of the chemicals ever found in the wells, water entering the system reached as high as 1,186 ppt.

By itself, Warminster’s Well No. 26 nearly eclipsed that amount — providing approximately 250,000 gallons of water with chemical contamination as high as 1,440 ppt.

The ATSDR said it has also collected historical well information from the water authorities for use in previously scheduled public health assessments for the bases, but also potentially for more complex analysis of the PFOS and PFOA contamination in the future.

“ATSDR will use this (historical) information in continued discussions about what might constitute feasible and potentially helpful future activities,” Cope wrote.

A moving target

The difficulty of analyzing how much PFOA and PFOS a community could have been exposed to is compounded because the chemicals have a notorious reputation for being hard to track.

Robert Delaney, an environmental quality specialist with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, has been helping investigate perfluorinated chemical compound contamination around the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base in that state. He said the chemicals are highly unusual, spreading widely and popping up in areas where officials didn’t expect them.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” Delaney said. “On the base, we have sampled hundreds of wells and we’ve found about three wells on the whole base that weren’t contaminated. ... We’re now finding (the contamination) expanded beyond the boundaries of what we thought, and so we’re trying to get a handle of how big it is.”

A major part of the problem, according to Delaney, is that some ingredients used in firefighting foams can break down into PFOA, PFOS and dozens of similar chemicals at different rates, depending on the product used and the environmental conditions in the soil and groundwater.

The fact that two wells have similar amounts of PFOA and PFOS at a point in time doesn’t mean that has always been the case or that it will stay that way. The contaminated groundwater could be just arriving or leaving, or the foam’s ingredients could be just beginning to break down into the chemicals or nearing the end of that process.

“The chemicals can be out there in a different form, just waiting to break down and then show up in your sample or your well,” Delaney said.

Christopher Higgins, an associate professor with the Colorado School of Mines’ Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, said it would be difficult to prove whether differing amounts of chemicals in Horsham, Warminster, and Warrington could explain the different cancer rates.

“There are so many factors for how long the compounds take to move from (where they were used) to a well or drinking supply,” Higgins said. “Without knowing when that happened it’s very difficult ... to say what’s causing cancer rates. If there is a cause; if it’s not just totally random.”

A more thorough review

Analyzing cancer rates by township and reviewing the histories of the three public water systems still leaves questions.

- Despite Horsham’s most contaminated well only coming online in 2001, testicular cancer rates in the 19044 ZIP code fell dramatically in the last two decades -- from double the state rate in 2005 to nearly 43 percent lower in 2013, according to the ATSDR report.

- In places where cancer rates increased for men, they often fell for women.

- Rates of kidney cancer, which has been linked to PFOA by the largest human health study conducted so far, were at or below normal for both Warminster and Horsham.

For their part, public health officials involved locally said additional studies could be coming.

“Given these findings and given the long history of environmental contamination in this area, we are certainly looking at (the ATSDR report) as a first cut,” the state health department’s Watkins said in August.

In an email, the ATSDR’s Cope echoed what Watkins said in August: that the two agencies are considering further studies in the area.

“PADOH has asked ATSDR about a long term health study that could include exposed Pennsylvania residents,” Cope wrote. ”(The two agencies) are continuing discussions about possible future activities... These discussions are occurring between PADOH and ATSDR at both the leadership and staff levels.”

Cope also said the state Department of Health asked the ATSDR in July to consider including local residents alongside any study of health effects at the Pease International Tradeport in New Hampshire, another site of PFOA and PFOS drinking water contamination.

Former Pease employees have had their blood tested by the New Hampshire Department of Health, something area residents such as Larry Menkes want here.

The 77-year-old Warminster resident, who serves on the town’s Environmental Advisory Council, is trying to raise more than $400 to get blood tests for himself and his wife.

Menkes’ medical records show he was diagnosed with bladder cancer in 2012. He said his wife, Jacqueline, also began experiencing health problems earlier this year, including gastrointestinal and thyroid issues.

“I think we need some people to really have the test done early to show people what the blood levels are in some of us,” Menkes said.

According to Alexander, the University of Minnesota professor, those kinds of studies are more valuable than simple cancer cluster studies. But, he also warned that because of the lack of existing research on PFOS, even such a study couldn’t be considered scientifically definitive.

Unfortunately, Alexander said, he believes it could be some time — perhaps decades — before researchers have a clear picture about what illnesses the chemicals can cause, if any.

“That’s a real frustration for people in a community like (Horsham, Warminster and Warrington),” Alexander said. “They want an answer and they want an answer now. And nobody in good conscience can give them an answer.”